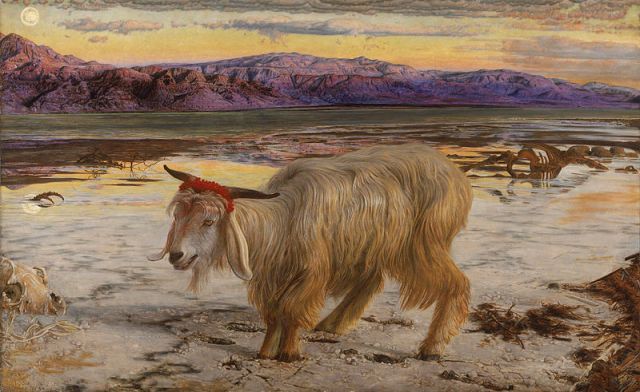

Michael the Archangel by Guido Reni

The following are an extensive list of thoughts on Luke 3 to 4, arising from the Twitter Bible study, #Luke2Acts. I hadn’t originally planned to post this. However, as I got rather absorbed into these two chapters, I thought that some of the readers of this blog might appreciate if I shared a few of my reflections. As usual, take these suggestions with a pinch of salt and exercise caution when running with any of the possibilities here. That said, I get the distinct feeling that there is a great deal in these passages that we haven’t yet discovered.

I would love to hear any further thoughts that my readers might have in the comments. Also, if you find any of this interesting, you should join the discussion on Twitter. I have no current plans to continue posting on the subject here.

***

Once again, Luke sets the scene within the context of the wider world and its rulers and empires. A new ruler is coming onto the world stage and, from this time onwards, the nations and their rulers must reckon with him.

While the other gospels don’t mention Pontius Pilate until the time of Jesus’ trial, Luke introduces him as a character here. He also speaks of the surrounding regions, establishing a more cosmopolitan context.

Seven historical figures are mentioned—Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate, Herod, Philip, Lysanias, Annas and Caiaphas—rooting the narrative in a clear historical context too. It is easy for us to forget that history is measured relative to persons, rather than according to an abstract metric. To enter into history is to take up a position in the world of human affairs. ‘In the 2014th year of our Lord, and the 53rd year of the reign of HM Queen Elizabeth II, Barack Obama being president of the United States…’

***

‘The word of God came to John the son of Zacharias’—this is a familiar formula for the word of YHWH coming to the prophet. Note the fact that many of the prophets’ books are introduced with a similar expression. This formula is often contextualized by mentioning the reign of particular kings or rulers—often foreign—along with the name of the prophet and his father (Hosea 1:1; Amos 1:1; Micah 1:1, Zephaniah 1:1, Haggai 1:1; Zechariah 1:1; etc.). The prophets operate within an international context, speaking as God’s representatives to kings and rulers of nations. Unsurprisingly, John the Baptist is later imprisoned for speaking out against Herod (Luke 3:19-20).

***

‘Baptism of repentance for the remission of sins’—as N.T. Wright observes, the ‘remission of sins’ refers to God’s restoration of sinful Israel. The baptism was an act of national, not just private, repentance. This baptism occurred in the wilderness on the far side of the Jordan. Those who came to be baptized by John had symbolically to leave the land and reenter it by washing. John is one preparing the way for the returning king in the wilderness. He baptizes in the wilderness so that people can be brought into the land by Jesus (Joshua). John was from a priestly family and his actions should be understood in light of this. Baptism wasn’t something that arose out of the blue, but something related to rites of the Levitical system.

***

John the Baptist here raises the question of who the true children of Abraham are, a question that is central to Romans and Galatians. In using the expression ‘brood of vipers’ he is effectively declaring that the multitudes coming to him are the seed of the serpent (cf. Genesis 3:15) as opposed to the children of Abraham.

‘God can raise up children to Abraham from these stones’—God later raises up Christ from the stone grave as Abraham’s true heir. Abraham himself is described as a rock in Isaiah 51:1-3. Israel is raised up from the rock and God can do the same thing again.

***

‘The ax is laid to the root of the trees’—The trees are going to be chopped down at their very roots, not just at the trunk. Once again, the image comes from Isaiah (10:33-34). Those who know the Isaiah reference will recognize that what comes next is a rod growing from the ‘stem of Jesse.’ The kingdom is cut down beyond even David and a new David will arise, like life from the dead. The image of the ax and the trees is also reminiscent of Psalm 74:1-7, where the trees are associated with the temple. The nation and its temple will be cut down by the ax of the Romans in AD70 and burned.

***

Jesus is ‘mightier’ than John. Here Jesus is presented as a powerful warrior. Once again, we are in the world of Isaiah allusions here. Jesus is like the depiction of the Lord as a mighty warrior, singlehandedly working salvation, treading out the winepress in the day of his vengeance in Isaiah 63:1-6. John the Baptist isn’t worthy to loose Christ’s sandals for this treading. The references to strength are significant. The Hebrew meaning of Gabriel’s name also refers to might and strength. The scene is being set for a showdown with the strong man who holds the world in bondage (cf. 11:21-22). More on this later.

***

I discuss the possible meaning of the threshing floor here:

Our first introduction to Christ in the New Testament through the testimony of John the Baptist is as the one who winnows at the threshing floor (Matthew 3:11-12):

“I indeed baptize you with water unto repentance, but He who is coming after me is mightier than I, whose sandals I am not worthy to carry. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. His winnowing fan is in His hand, and He will thoroughly clean out His threshing floor, and gather His wheat into the barn; but He will burn up the chaff with unquenchable fire.”

Christ is the one who works the threshing floor, much as he is the one who treads out the grapes and the winepress in Isaiah 63:1-6 and Revelation 14:14-20 (where he also reaps the wheat). In our worship we meet with Christ our kinsman redeemer on the threshing floor where the wheat and the chaff are separated by the Word of God.

Only a fairly dull ear would miss the heavy allusion to Malachi 3:1-3:

“Behold, I send My messenger, and he will prepare the way before Me. And the Lord, whom you seek, will suddenly come to His temple, even the Messenger of the covenant, in whom you delight. Behold, He is coming,” Says the LORD of hosts. But who can endure the day of His coming? And who can stand when He appears? For He is like a refiner’s fire and like launderer’s soap. He will sit as a refiner and a purifier of silver; He will purify the sons of Levi, and purge them as gold and silver, that they may offer to the LORD an offering in righteousness.

The temple of Malachi 3 is replaced with the threshing floor in Matthew 3. Christ, however, is the one who purges both the temple and the nation of Israel. He is the one who separates wheat from chaff, burning the latter and gathering the former.

Given our previous observations about the significance of the removal of sandals, I would be surprised if it were accidental that John the Baptist consistently mentions the fact that he is unworthy to carry or to loose the sandals of Christ (Matthew 3:11; Mark 1:7; Luke 3:16; John 1:27). The impression given is that Christ’s sandals are being removed for some reason. I suggest that this removal of the sandals has to do with Christ’s treading out of the grain in the holy place.

***

Herod the tetrarch persecutes John the Baptist at the instigation of his wife, Herodias. The parallel to Jezebel’s instigation of Ahab’s persecution of Elijah (in whose spirit and power John came—1:17) should be clear.

***

Jesus is baptized when all of the people have been baptized, presumably suggesting that it was not just as one of the crowd. Is the suggestion that Jesus is the one who completes the full number? I am not sure whether Luke intends this, but the Flood account is brought to my mind here. When all have entered the ark, God closes the door. Then the heavens are opened. The Holy Spirit later descends upon Jesus like a dove, like the dove descended on the new earth after the Flood (I think that Luke intends this much, though doubt that he intends a wider set of Flood allusions). Father, Son, and Spirit are all seen within a single event.

The Spirit hovering over Jesus as he comes out of the water also recalls the Spirit’s presence at the first creation of the world. Notice the way that Isaiah 63:11-14 brings together the themes of creation with the event of the Red Sea crossing—‘brought out of sea’ as the land was raised up on the third day; ‘put Holy Spirit within them’, like breathing the breath of life into Adam; ‘dividing the water’, like the waters above and below on the second day; ‘through the deep’, like the deep of the original creation; ‘causes him to rest’, the creation Sabbath. The original creation was created out of water. The world after the Flood was created out of the waters. Israel was formed out of the waters of the Red Sea and Exodus. In Jesus’ baptism we see that the new creation is formed out of the waters too.

***

Why is Jesus baptized by John? Various reasons can be given and different gospels emphasize different things. It creates continuity between the ministry of John the Baptist and Jesus. Just as Moses and Joshua (Joshua 1) and Elijah and Elisha (2 Kings 2) passed the baton of ministry on the far side of the Jordan, so John passes the baton of ministry to Jesus at the same place. Jesus has same name as Joshua and leads us into the Promised Land. His ministry is compared to that of Elisha at various points in the gospel of Luke. Before Jesus, Elisha was the most prominent miracle-worker in the land.

In being baptized with the rest of the people, Jesus identifies with them and identifies them with him. He is the one who will lead them into the Promised Land. As the leader of the people he also takes their state upon himself, along with all of their history. He enacts the repentance of the nation that he represents by being baptized with John’s baptism.

At his baptism, Jesus is set apart as a priest. Jesus began his ministry at around thirty years of age, which is the age that the priests began. As Leithart observes in detail (and in even more detail in his superb book, The Priesthood of the Plebs), Jesus’ baptism was a baptism into priesthood (cf. Exodus 40:12). The fact that a genealogy follows should be related to the fact that Jesus is entering into priestly ministry at this point. The genealogy marks him out as qualified for priesthood.

The baptism is a confirmation both to Jesus and to John of Jesus’ status as the Son of God. In John’s gospel, the descent of the Spirit upon Jesus is that which manifests Jesus to John as the Son of God (John 1:29-34). This marks the definitive beginning of Christ’s ministry, but also demonstrates that John’s ministry has achieved its purpose. It is important to remember that a qualification for the Twelve was having been there since baptism of John (Acts 1:22). Each of the gospels starts with the witness of John.

By being baptized in the waters of the Jordan, Jesus also sanctifies the waters of Baptism as the means of his new creation, just as it had been the primary means of previous creations. Jesus takes up the natural element of water and glorifies it in using to form his kingdom. Tertullian’s approach to these themes is worth revisiting here. In being baptized, Jesus also sets the example for all of us to follow in his steps.

***

Jesus’ story is a story of three baptisms: his baptism of anointing and manifestation in the Jordan; the baptism of his death; and the baptism of the Spirit that he performs at Pentecost. In Jesus’ baptism he gathers up the story of all of the great ‘baptisms’ of the Old Testament (the creation, the Flood, Red Sea, baptism into priesthood, the ritual washings, Elijah crossing the Jordan, etc.) into his story. He takes up the baton from the last great Old Testament prophet—John the Baptist. He identifies with a sinful people and then, out of their broken history he forges a new one.

Our baptism is how we are plugged into his Baptism—we are baptized into him as Israel was into Moses, the one drawn from the water. We are baptized with him in Jordan, anointed with his Spirit for ministry and declared to be God’s beloved children. We are baptized with him in his death, dying and rising again to new life. We are baptized with his baptism of Pentecost, clothed with the mantle of the ascended Christ’s Spirit and made one body in him. The story of all things is gathered together and summed up in the baptized Christ and we in him.

***

The descent of the Spirit upon Jesus in his Baptism should be related to the later descent of the Spirit upon the Church at Pentecost. As Christ ascends into heaven, his Spirit descends upon the Church, like the mantle of Elijah fell to Elisha and Elijah received the firstborn portion of Elijah’s Spirit when Elijah ascended in 2 Kings 2. Elijah’s ascension is Elisha’s pentecost.

***

The genealogy has 77—7×11—names. We have already seen that Anna is a widow of 84—7×12—years. Jesus brings in the twelfth seven and comes as the kinsman redeemer to his widowed people.

***

The genealogy moves in the opposite direction from most lengthy biblical genealogies. I’m not sure what to make of this. By presenting Jesus at the start, is Luke highlighting the convergence of all upon him? While genealogies usually branch out and the last person within them is merely one twig in a larger tree, here Jesus is the rod from which the rest of the tree is ordered. While he may be descended from many, many previous generations, he is the new root.

***

While Matthew’s genealogy starts with Abraham, Luke’s traces Jesus’ line back to Adam and God. While Abraham represents Israel, Adam represents the entire human race. The fact that Jesus is the Son of God is underlined in these earlier chapters of Luke (1:35; 2:49; 3:22, 38; 4:3).

***

Different language surrounding Jesus’ entry into the wilderness in gospels is fascinating, as each sets up different echoes.

Matthew: ‘led up to the wilderness by the Spirit.’ The allusion here seems to be to Israel’s being ‘led up’ out of Egypt into the wilderness by the Spirit (the pillar of cloud and fire) in the Exodus.

Mark: ‘the Spirit drove him out into the wilderness.’ This is reminiscent of David being driven out from Saul’s court into the wildernesses (1 Samuel 23:14-15, 24-25; 24:1; 25:1; 26:2-3). While in the wildernesses, David lived with the wild beasts (the Gentiles), and resisted the temptation to snatch the kingdom for himself before it was time (I might post more on Mark’s account in a separate post).

Luke: ‘Jesus, being filled with the Holy Spirit … was brought in the Spirit into the wilderness.’ This is the language of the prophet caught up and transported by the Spirit (cf. Ezekiel 3:14). Note the similarities with Luke 2:27, where Simeon comes by the Spirit into the temple. Another interesting parallel can be seen in Revelation 17:3, where the seer John is carried away in the Spirit into the wilderness, where he encounters the Whore of Babylon on the Beast.

There is a priest (Exodus) to king (kingdom era) to prophet (later history of Israel and Judah) pattern in the Synoptic gospels and this be seen as one instance of it.

***

Perhaps there is a subtle allusion to the hand of the Lord coming upon Ezekiel and carrying him in the Spirit into the wilderness valley of dry bones (Ezekiel 37:1). There is a pattern in Ezekiel. Ezekiel is first transported by the Spirit into the wilderness (37:1), then to a very high mountain (40:2), then to various extremities of the temple (40:17, 24, 28, 32, 41:1; 42:1; 43:1; 44:1, 4). This visionary journey is mirrored in Revelation: wilderness (17:3), mountain (21:10), temple (21:22ff.), the mountain and the temple being closely related, as in Ezekiel. The devil gives Jesus a false ‘apocalypse,’ a twisted alternative to the visions of God’s future received by the prophets.

***

The parallels between Jesus and Ezekiel are significant. Ezekiel is about thirty years of age (Ezekiel 1:1). He sees the heavens opened and visions of God (1:1). He hears a voice of one speaking (1:28). He is addressed as ‘Son of man’ (2:1) and the Spirit comes upon him (2:2). He is then fed by the word of God (3:1-3) and brought on a visionary journey (3:14, etc.). In 2:9, Ezekiel is handed the scroll of prophecy, the word of God, which he then eats. The prophets were fed by the Word of YHWH. Ezekiel eats the scroll in Ezekiel 3:1-3, as does John in Revelation 10:8-11. He receives the word of God into his mouth, which he will then speak forth. In Luke 4:17, Jesus is handed the scroll of prophecy. He then proceeds to speak the word of prophecy as a word that he incarnates. The people marvel at the ‘gracious words which proceeded out of his mouth’, alluding to the concluding words of Deuteronomy 8:3, which Jesus didn’t quote in verse 4.

***

There is possibly an Exodus pattern here: after the water crossing/baptism (Red Sea), there is a period in the wilderness associated with miraculous bread (manna), coming to the mountain (Sinai), and then the temple (tabernacle).

***

Notice also the pattern in the story of Elijah. During the drought the Spirit leads Elijah out of the land, where he miraculously ‘makes bread’ from pottery (1 Kings 17:8-16). Later Elijah is fed with miraculous bread baked on ‘hot stones’ (19:5-8), which gives him strength to go without food for forty days and nights. Both of these events are accompanied by the word of YHWH. He then goes to the mountain of Sinai, where he is given a vision and commission for the future of the kingdom.

***

Refusing to eat of the food of the land bearing the curse, the prophet is fed by heavenly bread. The Israelites rejected the old leaven and ate manna—bread from heaven. Moses went without bread for forty days on the mountain, receiving tablets of ‘stone’ from God. David ate the holy bread of the tabernacle (1 Samuel 21:1-6). Elijah is fed by the ravens, then by the miraculous bowl and jar, then by the bread from the angel. The devil wants Jesus to produce bread from his curse-bearing territory, rather than relying by faith upon God’s bread. The wilderness becomes the source of a feast both in Ezekiel (39:17-20) and in Revelation (19:17-21), after the great victory has been won.

***

Luke has already mentioned a miraculous transformation of stones in 3:8. Also notice that in Luke the devil calls Jesus to produce bread from a single stone (v.3), rather than from many (Matthew 4:3). I am not sure what to make of this. Should the stone be connected with the stone of Jesus’ tomb, Jesus’ body being the bread? From the (grave)stones, as in Ezekiel 37:12, God will raise up a new loaf, the true children of Abraham.

***

Christ has been connected with Adam in the verse immediately before the temptation account. He is then described as being filled with the Spirit (the breath) of God. Like Adam, he is tempted by the devil to eat forbidden food and to jump the gun on God’s kingdom plans. Like the serpent in the Garden, the devil seeks to twist God’s word. The last Adam resists in the hunger of the wilderness, what the first Adam failed to resist in the plenitude of the Garden. As Peter Leithart observes, the role played by the Spirit in this narrative should be related to that of Eve. The Spirit is the ‘helper’ of Christ.

Is there a way that we could give more substance to this suggestion? Perhaps. Consider the association between the dove and the beloved in Song of Solomon. ‘Dove’ is the King’s ‘pet name’ for his Bride (1:15; 2:14; 4:1; 5:2; 6:9). The dove is also associated with love, the time of love (2:12), and with the eyes of both the King (5:12) and his Beloved (1:15; 4:1). The dove is a messenger of love and the eyes of the lover are like those of fiery doves (note the connection between the mode of the Spirit’s appearance at Jesus’ baptism and at Pentecost). Coming as a dove, the Spirit is the ‘bodily form’ of the Father’s love for his Son. The Spirit is the personal gift of the Father’s love.

The Spirit, however, is also associated with the Bride (cf. Revelation 22:17). The Spirit forms a Bride for the Son. Even when spoken of using masculine pronouns, the Spirit is associated with feminine themes, hovering over the womb of the original creation (Genesis 1:2), being like an eagle hovering over its young (Deuteronomy 32:11), and overshadowing the womb of Mary (Luke 1:35). In Revelation we see the Bride, the Lamb’s wife, descending out of heaven, having the glory of God (Revelation 21:2, 9-11). This is a glorified form of the descent of the Spirit upon Christ at his Baptism. The Church, as the Bride of Christ formed in and by the Spirit by the will of Father is the expression of the Father’s love for his Son. Given the Spirit’s relationship to the Bride, the symbolic connections between the dove and the Beloved, the baptismal descent of the Spirit and the eschatological descent of the Bride, and the Adamic themes within the passage, I believe that we are justified in associating the Spirit with Eve here.

***

Seeing all of the kingdoms in a moment in time might be like the visions in Daniel of the different successive empires.

The devil is the ruler of the wider empire, making him the direct adversary of Gabriel, who has appeared earlier to announce the births of John and Jesus. John’s baptism of the mightier Jesus leads to this conflict, as Jesus fights on Gabriel’s behalf against his great adversary. Keep in mind the points that I made earlier about the emphasis upon ‘might’.

This should be related to the role of Michael—the heavenly prince of Israel—in supporting Gabriel against the opposing kings in Daniel 10:13, 21. Michael is connected with the Angel of YHWH (Zechariah 3; cf. Jude 9). In turn the Angel of YHWH or the ‘Angel of the Covenant’ is connected with Christ (I comment on the Angel of YHWH here and here). Malachi 3:1 is a key verse here, as it relates the coming of the Angel (or Messenger) of the Covenant to the ministry of John the Baptist and Christ:

“Behold, I send My messenger,

And he will prepare the way before Me.

And the Lord, whom you seek,

Will suddenly come to His temple,

Even the Messenger of the covenant,

In whom you delight.

Behold, He is coming,”

Says the Lord of hosts.

The Lord, the Messenger of the covenant, is Christ. Once this has been appreciated, a very interesting picture starts to emerge. Gabriel tells Daniel that Michael will stand up at some point in the future (Daniel 12:1). Luke presents us with the coming of the mighty champion who will equip Gabriel to defeat the devil and his princes. John speaks of Michael and his angels fighting against the dragon (the fully grown serpent) in Revelation 12:7-9.

***

The references to angelic rulers, the heavenly army, and conflict with the devil in these early chapters of Luke should make clear that there is a battle of spiritual powers occurring throughout the gospel and that we shouldn’t merely focus upon the surface events. The devil’s second temptation is an invitation to Jesus to rule under and with him, rather than under the Father. This temptation would be a way for Jesus to avoid the great battle of the cross.

***

When Jesus resists his second temptation, the devil tempts Jesus to throw himself down from the pinnacle of the Temple, to cast himself out of the realm of God’s presence, assuring him that the angels will protect him, much as Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego were protected in the fiery furnace. If Jesus won’t rule alongside the devil on the devil’s terms, the devil assures Jesus that God will protect him if he exiles himself. Rather than plundering the strong man and resisting the devil’s claims over God’s house (we should recall Ezekiel’s visions of the Temple as a place of idolatrous devil-worship in Ezekiel 8-11), Jesus would be protected if he abandoned the house to the devil. It would be so much easier for Jesus if he just cast himself away from Israel.

***

All of Jesus’ responses to the devil involve quotations from the book of Deuteronomy (8:3; 6:13; 10:20; 6:16) and all refer to the testing of Israel in the wilderness.

***

The devil departs from Jesus ‘until an opportune time’, presumably Gethsemane. Observe the emphasis upon trial (a more appropriate word than ‘temptation’) in the Garden of Gethsemane (Luke 22:39-46—the same word for ‘trial’ is used here as in 4:13). Perhaps this should be related to the ‘time of trouble’ spoken of in Daniel 12:1. Perhaps there is also some relationship between the trials in the wilderness and the ‘trials’ leading up to and upon the cross.

Here is one possibility. The first trial is in the Garden of Gethsemane. Jesus must live by every word of the Father. The Father’s word takes the form of a ‘cup’ that he must drink (22:42). While Jesus could reject the cup of his Father and eat the portion of the devil, he chooses to live by the word of his Father. The second trial relates to his claims of kingship while before Pilate and Herod (22:6—23:12). The kingdoms of this world cast their judgment on Christ, ridiculing and condemning him. Jesus could assert his reign in a demonic fashion, but he accepts the crown of thorns and is raised up on the cross. The third and final trial occurs while Jesus is on the cross. Those watching the crucifixion, the rulers among them, the soldiers, and even one of the criminals crucified with him call him to save himself (23:35-39), to cast himself down from the cross and to abandon the temple and his mission. As Jesus perseveres with his mission through this trial, the veil of the temple is torn in two (23:45) and the strong man is decisively defeated.

***

Jesus’ reading from Isaiah brings together Isaiah 61:1-2 with 58:6. The acceptable year of the Lord might be a reference to the Jubilee (Leviticus 25:8-17), which would fit well within Luke’s emphasis upon economic themes. Jesus is bringing the release of all debts. It would also relate to the Sabbath and true fast spoken of in Isaiah 58. Jesus doesn’t quote the end of Isaiah 61:2, with its reference to the ‘day of vengeance’. His current ministry is one of blessing and restoration. The day of vengeance comes later for Israel in AD70 and, unsurprisingly, the expression occurs in that context later in Luke 21:22. Jesus’ proclamation of liberty should be related to his defeat of the devil’s power over the land, restoring the land to its original owners.

****

Jesus stands up to read and then sits down to teach. How would this posture shape the way that we regard the place of the preacher? It is also interesting to observe that Jesus seems to be a regular reader at the synagogue. Jesus may have been one of a handful of members of the synagogue who were literate.

***

The people of Nazareth point out that Jesus is Joseph’s son. With this they attempt to exert some authoritative claim upon Jesus. ‘Physician, heal yourself!’—the people of Nazareth believe that Jesus owes them special treatment on the miracle front. He should recognize the greater duty that he has towards his own country, literally his ‘fatherland’ (v.23). Jesus challenges this claim with the examples of Elijah and Elisha.

***

I have already suggested that verse 22 should be related to Jesus’ rejection of the first temptation in verse 4. Jesus is ‘fed’ by the scroll of the prophet and bears those words on his mouth. Jesus is the one by whom the true bread of God’s Word is given, rather than the bread of the devil. I believe that the attempt to throw Jesus over the brow of the hill in verse 29 should be related with the third temptation. Jesus’ own people seek to ‘cast him down from the Temple’, but he does not allow Israel to cast him away, which would have been the easy way out of the situation. This leaves us with the question of whether the second temptation is alluded to between these two. I believe that it is. Specifically, Jesus rejects the attempts of his own people to get him to serve them, serving God alone. Rather than seeking demonic mastery over the world, he chooses to minister deliverance to Gentiles, as Elijah and Elisha did.

***

The reference to Elijah and Elisha here is significant, and not merely on account of the numerous allusions that have already been made to them in the book so far. As Leithart’s chiasm make clear, in the corresponding passage in the chiasm, there are healings that are reminiscent of Elijah and Elisha. The healing of the centurion’s son (7:1-10)—a miracle done at a distance for a military man of a foreign power—can be related to Elisha’s healing of Naaman the Syrian, another foreign military man, which Jesus mentioned in verse 27 (cf. 2 Kings 5:1-19). The raising of the dead son of the widow of Nain (7:11-17) relates to Elijah’s raising of the widow of Zarephath’s son (1 Kings 17:17-24). The widow of Zarephath is mentioned in verse 26.

***

Having faced the devil in the wilderness, Jesus now faces demons in the synagogue (verse 33). The devil’s forces are occupying the heart of Israel’s places of worship, threatening to render it a desolate place. We don’t see demons much in the Old Testament. They are largely associated with the wilderness and abandoned locations (Isaiah 13:21; 34:13-14; Luke 11:24). Widespread demonic possession isn’t the norm. However, Jesus performs exorcisms wherever he goes. Perhaps we should relate this to the story of David and Saul. After David has been anointed by God’s Spirit, a distressing spirit troubles Saul and David has to minister to him (1 Samuel 16). As Christ is anointed by the Spirit, he will play a similar role for Israel, causing the distressing spirits to depart from the people.

***

We find a reference to Simon here, without any previous introduction. Luke seems to presume that Simon will be known to his readers (cf. 1:4). What other knowledge does he presume along the way? Also notice that Simon’s wife is spoken of here, even if only to mention that she has a mother. In light of Luke 18:28-30, should we presume that Peter left his wife behind to follow Jesus around? Was she one of the women who helped to fund Jesus’ ministry (8:1-3)? She later accompanies Peter as a fellow worker in 1 Corinthians 9:5.

***

Simon’s mother-in-law’s fever is spoken of like a form of possession. It ‘afflicts’ her, Jesus ‘rebukes’ it, and it ‘leaves her’.

***

Having faced the trial of the prince of the demons at the beginning of the chapter, Jesus spends much of the rest of it defeating his minions. The reference to the setting of the sun in verse 40 is interesting (see also Matthew 8:16-17; Mark 1:32-34). It seems strange that such a detail would be recorded for us. I suspect that there is a miniature resurrection sequence here. The Sabbath sunset has just fallen and Jesus performs a dramatic cluster of healings and exorcisms (vv.40-41). When it is day, Jesus disappears to a deserted place and the crowds seek for him, but he won’t stay with them. As the sunset falls on the Sabbath, the first day of the week begins and Jesus’ strength is shown against the forces of the devil. In the early morning of the first day of the week—later the day of resurrection—Jesus can’t be found and has to be sought by the crowd. He then declares his mission and the fact that it will take him away from them.

This resurrection pattern is more pronounced in Mark 1:32-39. In Matthew 8:16-27, Jesus’ healing is connected with Isaiah’s prophecy of Jesus’ bearing of our infirmities and sicknesses, something which is primarily associated with the cross (v.17). Then Jesus descends into the deep, as the waves cover the boat while he is asleep (vv.23-24). He then arises, rebukes the waves and challenges them for their little faith (v.25-26).

***

Anyway, those are my rough thoughts so far. I would love to hear any ideas that you might have in the comments!