The following is a long excursus from my previous post on the meaning of Mark’s account of Jesus’ time in the wilderness. As it grew longer, I decided to remove it from that piece and post it separately. Joey Cochran suggested another connection within the Markan account to me: that this is an allusion to the scapegoat. I think that this is exactly correct and it is one that helps to align a broader constellation of allusions and echoes. As yet, I don’t know exactly how to fit all of the data together as the theme is one that undergoes unusual developments. In the remarks that follow, I will lay out some of the relevant biblical details and suggest some theories that account for certain dimensions. I will leave it to you to propose further ways of filling out the picture in the comments.

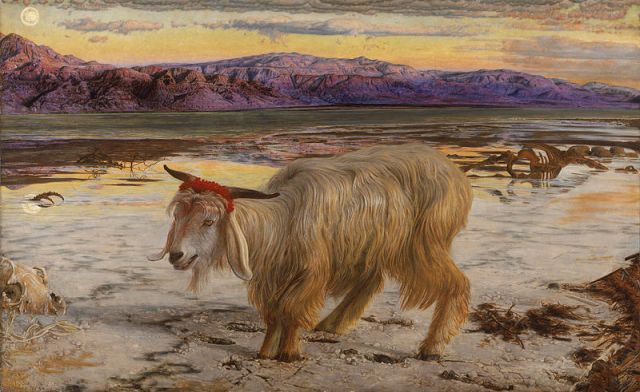

The Day of Atonement or Day of Coverings ritual (Leviticus 16) involved a goat being sacrificed as a sin offering for the congregation of Israel (v.15) and another goat being sent away into the wilderness by the hand of a suitable person (vv.20-22). A lot is cast between the two of them to determine which will do which: one is for YHWH and the other is for Azazel. One of the goats—the goat for YHWH—is killed for the nation as a sin offering (along with a bull for the High Priest) and its blood is used to sprinkle on and before the mercy seat and the golden altar of incense, releasing them from their defilement and removing any judgment resting upon the world order that they symbolized. The High Priest confesses the iniquities of the nation over the other goat—the goat for Azazel—and sends it off into the wilderness by the hands of a suitable person. This goat, to prevent its return, would typically be thrown over a precipice. After this had been done, the fat of the goat and bull of the sin offering for the people and the High Priest would be burnt on the altar. Then the flesh of the sin offering, its skin, and offal would be burnt in a clean place outside of the camp and no one would eat any of it. Through the Day of Atonement, the world would be cleansed and the nation would be released from their sins as they were confessed over the scapegoat.

The scapegoat is literally described as being ‘for Azazel’, a word that only occurs four times in the whole Bible, all within Leviticus 16 (vv.8, 10, 26). Various suggestions have been given for the meaning of this. It is interesting that the name ‘Azazel’ appears as the name of a chief demon condemned to the wilderness in the book of Enoch (Enoch 8:1; 9:6; 10:4-8; 13:1-2; 54:5; 55:4; 69:2). More generally, demons are associated with goats (Leviticus 17:7; Isaiah 13:21; 34:13-14; 2 Chronicles 11:15) and with the wilderness (Luke 11:24; Revelation 18:2).

As a symbolic and sacrificial animal, the goat is related to the ruler of the people (Leviticus 4:22-24) and presumably also to the congregation as a whole as a civil polity. The common symbolic root that accounts for this meaning and also for the demonic connotations of the goat is that of governmental authority and power. The word `attuwd, for instance, means both he-goat and leader (cf. Isaiah 14:9; Zechariah 10:3; Daniel 8:5, 8, 21). A word for ram, ‘ayil, has a similar double meaning.

There is a Day of Atonement pattern at work as Ishmael is sent by Abraham, playing the role of the High Priest, into the wilderness by the hand of Hagar (Genesis 21:8-21). In a passage that closely echoes the passage concerning Ishmael, Abraham them offers up Isaac (Genesis 22). I’ve discussed the connections between those two accounts and the Day of Atonement a little here. Ishmael is the goat sent into the wilderness; Isaac is like the goat of the sin offering.

A more complex pattern occurs in the story of Esau and Jacob, which I discussed in connection with the Day of Atonement here. There is a wordplay on the description of Esau as a ‘hairy’ (sa`iyr) man, hair that is connected with the goat skin that is used to ‘cover’ up Jacob so that he can receive the blessing (note the strong sacrificial themes that I discussed in my post). The word sa`iyr also means he-goat, both the goat used for sacrifice and the demonic ‘goats’. Esau’s land was Seir (Se`iyr—Genesis 32:3).

Rebekah instructs Jacob to get two kids of the goats for her (Genesis 27:9). She makes a meal from them and dresses Jacob in the goats’ skins, so that he can be like his hairy brother. On account of the failure of her husband to favour Jacob as he ought to have done, Rebekah plays the role of the priest here, the two kids being related to her two sons. Esau is already like a goat and Jacob is dressed up in the skin of one.

Esau represents a crisis for the covenant. He is unfaithful to the covenant, despising his covenant birthright (25:29-34) and compromising the holiness of the covenant people by marrying Hittite women (26:34-35). If this weren’t bad enough, Isaac is happy to give the covenant blessing to the wicked son. Through her shrewd trickery, Rebekah ensures that faithful Jacob is the one who gets the blessing, as Isaac smells the pleasing aroma of the food and his son. The offering of Jacob to his father leads to blessing upon the land as Isaac is pleased with the food representing the fat of Jacob (27:27-29). However, the other kid, Esau, is told that his dwelling place shall be ‘away from the fatness of the earth and away from the dew of heaven above’ (27:39-40). The covenant order is restored as Esau is expelled from the scope of the covenant blessing, going to Seir.

Jacob, having symbolically offered his fat to his father, and being well received, then has to go ‘outside of the camp’. He comes to a place where he lays his head on a stone for the night. He has a dream of a ladder reaching to heaven, with angels ascending and descending, and YHWH above it. Later he calls the place Bethel and pours oil on the stone. Thus Jacob is like the goat of the sin offering.

Themes of competing heirs and goat themes also occur with Joseph and Judah. Joseph and Judah are competing for the covenant birthright (cf. 1 Chronicles 5:1-2). Both sons are represented by a kid of the goats. The tunic of many colours covered with the blood of Joseph—which is really the blood of a kid that has been killed—is presented to Jacob as false evidence of his beloved son’s death (Genesis 37:31-33). In the following chapter, Judah sends a goat by his friend’s hand to the supposed prostitute he had slept with in exchange for his signet and cord, evidences of his identity (38:17-23). Judah’s sexual iniquity contrasts with Joseph’s faithfulness in resisting Potiphar’s wife’s advances in the following chapter. Joseph, taken outside of the camp, is raised up and blessed, while Judah loses the birthright and is symbolically sent into the wilderness. As all of the heirs of Judah are bastards (Genesis 38), they cannot enter into the ruling congregation for ten generations (Deuteronomy 23:2; cf. Ruth 4:18-22).

David is the one who brings the tenth generation (according to Ruth’s genealogy). David is expelled from Saul’s court and spends time in the wilderness. My suggestion is that David is playing the part of the goat for Azazel, fulfilling the destiny of Judah. David is associated with goats at various points of the story. He is first found among the flocks (1 Samuel 16:11). He is described as ‘ruddy’, language that is only elsewhere used of Esau (1 Samuel 16:12; cf. Genesis 25:25). He is sent to Saul with a kid (1 Samuel 16:20). Michal, David’s wife, uses goats’ hair as a means to create an image of David to abet his escape (19:13). Saul later seeks for David in the Rocks of the Wild Goats (24:2).

The nation is under condemnation on account of the actions of Saul. David takes the identity of the nation upon himself as the anointed one and bears it into the wilderness. He faces off with the demonically-driven Saul and with the wild beasts of the Gentile rulers. He dwells in caves and wildernesses, places of death and demon possession. While doing this, he resists the various temptations he faces to grab the kingdom by force before it is given to him. By submitting himself to expulsion from the land, David bears its judgment, so that one day he can bring it blessing.

What might this mean for our reading of the baptism and testing of Jesus? We must recall that John was baptizing with a baptism of repentance for the remission of sins. Confession of sins was an essential part of John’s baptism (Matthew 3:6; Mark 1:5), as it was on the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16:21). John the Baptist—who, lest we forget, was from the priestly line—was playing a role analogous to that of the High Priest. Jesus here is the kid of the goats of Azazel who bears away the sin of the people (not quite the same ring as ‘the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world’, but there you go). In being baptized by the hands of the priest, Jesus takes upon himself the judgment lying over the confessing multitudes.

The blessing that Jesus receives at his baptism has Davidic resonances. God spoke of David’s line as his sons (2 Samuel 7:14; Psalm 89:26-29). David’s name likely means ‘beloved’. As the Father declares his Jesus to be his ‘beloved Son’, perhaps we can hear hints of David’s own identity. Jesus is the one who will inherit the throne of his father David (Luke 1:32). As with David, God drives his beloved Son into the wilderness.

Being ‘driven out’ into the wilderness by the Spirit, Jesus was being treated like a demon, being exorcised into their realm (cf. Luke 11:24), and sent to Azazel, the prince of the demons. He was receiving the condemnation of exile due to the sins that the multitudes were confessing. The encounter with the devil can be understood in light of this, as perhaps can the references to being cast down from high precipices. Jesus goes into the wilderness to the realm of Azazel, bearing the sins and judgment of exile due to the people. He passes through the period of trial and then returns victorious as the leader of a restored people. As he has borne the judgment due on the people, he can proclaim delivery to the captives.

Jesus later acts as the goat of the sin offering, his blood cleansing the world and the judgment it pronounces against humanity, and opening the way into communion with heaven. His body is offered outside of the camp (Hebrews 13:10-13). The flesh of the sin offerings contracted the defilement of the things that they cleansed. This defilement could only be removed by fire. The lesser sin offerings could be purged by cooking (cf. Leviticus 6:24-30), but could only be eaten by holy persons. However, the sin offerings for the Holy Place could never be eaten. Jesus bears the defilement of the Holy Place and exhausts it, bringing it to complete destruction, suffering outside of the city. As a result, as we feed on him, we enjoy an exalted priestly status. I suspect that there the notion of such a ‘two stage’ atonement might be worth exploring.

Thoughts?

I wonder whether similar Day of Atonement dynamics may be going on in the story of Elijah and Elisha. Elijah is described as a ‘baal (lord) of hair’ in 2 Kings 1:8. In 2 Kings 1, Ahaziah sends men to inquire of Baal-Zebub, the chief of the devils (Luke 11:15), for him. However, the men meet Elijah, the goat-like ‘baal of hair’ instead. In the following chapter (I’m following Peter Leithart’s treatment here), in a sort of sacrificial sequence, Elijah and Elisha cross the Jordan. Elijah ascends in fire to YHWH. The ‘mantle-skin’ of Elijah, the ‘baal of hair’ falls to Elisha, who becomes the successor of Elijah.

As I have been alluding to on @M’s, there is also a connection with all these accounts to the prodigal son story in Luke 15. The younger son may be seen as Jacob and the older son may be seen as Esau.

The younger son is contrasted with Esau in that Esau left his family empty handed and returned with two wives, a full quiver of children, flocks, and servants. Though a prodigal in his own way wrestling with God and finally being brought to his knees in worship, he is returning wealthy physically and spiritually. The younger son in the prodigal son story leaves wealthy, loses his fortune, is brought to humility, and returns, hoping to merely be a servant. He returns from a far country, like allusions of foreigners in other texts (1 Kings 8:41, Prov. 25:25).

Zeroing in particularly on the older son, we see him coming out from the fields when the younger son returns. This is similar to where we find Esau as being the son who loved being out in the field (Gen. 25:27). This is where he was when he lost his birthright from being famished (Gen. 25:29), and this is where Esau was when Jacob and mom deceived Isaac (Gen. 27:5).

In the prodigal son story, the older son makes an important statement, “yet you never gave me a young goat, that I might celebrate with my friends” (Luke 15:29). This could be a subtle allusion to the older son perceiving himself to be like Azazel, the chief of demons, who might celebrate with his friends (other demons) with the scapegoat. This the older son says before the eyes of his father, in a self-deprecating sense and in comparison to the younger son, the older son feels slighted. Likewise, this is surely how Esau felt through much of his life. For Jacob was loved, but Esau was hated.

A positive end point in this story is that the Father assures the older one, “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours” (Luke 15:31). Likewise, with Jacob and Esau, there is a touching reuniting between the two after decades apart and later the two bury their father together.

Do we think Mark 1:40-45 is somehow related? Jesus removes the man’s uncleanness with a touch- something that should defile Him- and ends up forced out in the lonely places. He and the leper switch places through what He does so that he here becomes like the exiled Scapegoat, prefiguring how he will remove human uncleanness on the Cross.

The Day of Atonement aspects of the trial of Christ before Pilate is an interesting connection touched on by Leithart here http://www.leithart.com/2009/03/06/pilate-the-priest/ (I think he fleshed it out more elsewhere, but I can’t find it).

Pilate goes between the Jewish leaders and the inner area within the Praetorium with Jesus, in actions reminiscent of the High Priest. Pilate eventually brings out two sons of the flock of Israel, both named “Jesus son of the Father” and presents them to the crowd. No lots are cast, but the crowd chooses Barabbas and he is released into the crowd (which is acting as a sort of Azazel outside of the Praetorium, a demon-wilderness of an Israel possessed), and Jesus is brought to be sacrificed outside the camp as you described above.

Just as an exploratory thought… The fact that Jesus is driven into the wilderness but doesn’t give in to Satan in the three tests, that He later doesn’t get thrown off the cliff (another scapegoat action averted), and finally that the crowd, stirred up into a demonic frenzy, don’t release him but rather Barabbas, accepting their guilt back onto themselves instead of driving it away from them seem to point to Jesus being the Israelite who would finally be the sin offering that Israel needed, while the apostate generation was going to act as the scapegoat, in the large redemptive-historical drama that would unfold with the destruction of the Temple. The Israelites who repented were like the one who led the scapegoat out and had to be baptized to be allowed entrance back into the community of the sanctified. That might be an illustration of what Paul speaks of in Romans about God hardening Israel in order that the Gentiles might be saved. Israel had to act as the scapegoat for the sins of the world, while Jesus sanctifies the heavenly places with his blood, to grant access, etc. I do have a bad feeling, though, that this kind of reasoning was used to disastrous result in the sad history of Christian-Jewish relations… I don’t know, but I have a bad feeling about it.

Great thoughts, Will! Thanks for the comment.

My suspicion is that there are two related Day of Atonement cycles playing out here. The destiny of the sons of Abraham was to perform the role of both goats. Jesus does both. However, those who reject him no longer have a sin offering, but only the fate of the goat for Azazel. I wonder whether a careful study of the two women in the wilderness in the book of Revelation (the Woman of chapter 12 and the Whore of chapter 17) could be used to flesh this out.

Of course, as you observe, this needs to be handled exceedingly carefully.

Reblogged this on hilarionphang.

Hi Alastair,

I interpret the Scapegoat function to be that similar to a garbage truck that takes away the trash. (haha, but hear me out). Most people interpret it to mean the Scapegoat takes the blame and takes the punishment “cutting off,” but that’s not actually what the text is saying. From an article I wrote:

I blog at Nick’s Catholic Blog and have written a lot about the Atonement, especially the erroneous Reformed (and generally Protestant) view of Penal Substitution. I’ve covered numerous aspects of it, and I’m sure you’d be interested.

One Church Father I read (sadly, I forgot where) said that the two goats of Leviticus 16 represent Christ’s two natures, the Scapegoat represents the Divine Nature that did not suffer death.

Thanks for the comment, Nick!

Any thoughts on the Church as the Body of Christ being driven into the wilderness, out of the reach on Satan, in Revelation, as having a connection to this…those that are driven into the wilderness, being those that keep the covenant as Jacob did, and those that take the “mark of the beast” as those that break the covenant, as Esau did, being more concerned about the flesh thatn the spirit?

Quite a few. I wrote a section on this to include in the post above, but removed it before posting it. I would like to think about it further before saying anything. There definitely seems to be a connection.

Hi, I was wondering if youhave said anything further about my question about the mark of the beast, flesh vs. spirit.

Not too sure about the parallels with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob… but the parallel with Jesus being driven to the wilderness by the Holy Spirit…makes complete sense. God bless you and keep up the good work!

Some very interesting thoughts here, as well as in the comments. Thanks to all concerned. How best to understand the day of Atonement ritual isn’t yet clear to me. One idea I’ve considered, which someone could perhaps add to or highlight problems with, is as follows. The passover lamb is a substitutionary sacrifice. (If a lamb is slain in the firstborn’s place, then the firstborn of the house needn’t be slain.) But it’s not explicitly connected with sin in any way. Meanwhile, the goat for Azazel bears sin, but it isn’t offered as a sacrifice as such–at least, it’s not offered ‘before the LORD’ precisely, as far as I can see, because it bears sin. John then fuses the two ideas together in his reference to Jesus as “the Lamb of God [i.e., passover sacrifice] who takes away the sin of the world [i.e., goat for Azazel]”. Maybe that’s being too strict about what texts have to explicitly say though…I don’t know…

P.S. I wonder if it could be significant that after Jesus is driven into the wilderness and returns, the people try to throw him off a cliff?

Yes. There is a parallel between the three temptations and the subsequent events of the chapter, something I argue for here.

Apologies, I wasn’t clear. I was thinking more about how the goat for Azazel was (according to tradition) thrown of a cliff (not that I object to your other suggestion).

Yes, I think the connection exists. The cliff is significant, as it parallels with being thrown down from the extremity of the Temple, and later the cross.

I love that such obvious examples of typology are taken to be evidence of the prophetic nature of the Gospels that rewrite old events with new characters, change a few things and VOILA!

If I wanted to sell the gullible that a man being crucified would atone for my sins I would use the Azazel ritual too, the parallels between the two exist because the author of one had the other, older text, in front of him.

Crucifixion was just the chic way to get executed in Roman times, and wasn’t prophecied anywhere. Azazel ritual is not itself a prophecy so it being fulfilled at all is beyond suspicious, and obviously a case of using an old idea in a new way.

Copying. It’s not profound to twist the obvious fact around to make it seem like the Gospel writers did not have Leviticus to borrow the idea from.

Weep for Tammuz!

Whatever Jesus is said to have done does not seem to be as important as what he said, but since it is easier to believe that you only have to say you believe, and your sins are forgiven, although there is no agreement on how, why or if this works, is true.

It certainly is not how Jesus taught one should become a child of God. By obeying the Commandments such as “Our God is One God.”

Pingback: Video: What Is Paul’s Allegory of Sarah and Hagar About? | Alastair's Adversaria

This article has given me a new look at the goat of azazel. I work with a Seventh Day Adventist organisation. We have morning devotion before we start work.For the past month the Pastor has been teaching on the Cleansing of the Heavenly Sunctuary. What disturbed me is that he taught that the goat of azazel is satan who at some point will bear our sins. All along i thought Jesus was the scapegoat and that the two goats represented different functions the sacrifice of christ accomplished and not two petsonalities. Confused am researching on the topic. What do you think about this teaching by the Seventh Day Adventist Church

Pingback: What Is Paul’s Allegory of Sarah and Hagar About? – Adversaria Videos and Podcasts