Matt Armstrong has very kindly assembled all of my #Luke2Acts tweets from Luke 5-16 into a single document. I thought that I would order them into a less tweet-like form and post them here. You can see my other posts arising from this series here.

LUKE 5

The role that water, fishing, and water crossings play within the gospels should be attended to: it is highly significant. The Israelites in the Old Testament were led by shepherds. However, Jesus here calls his three closest disciples—Peter, James, and John—and they all happen to be fishermen. This should get our attention. He then connects their future work with the ‘fishing’ of men. Boats and fish hardly appear in the Old Testament at all, save in the book of Jonah. Why is this?

In the Old Testament, nations are compared to the sea, while Israel is the land. The nations are the realm of the fish and sea monsters, which can occasionally overwhelm the land. YHWH brought Israel ‘up out of the sea’, creating them as the ‘land’. In Jonah the sea, a boat, and a sea monster are given significance in connection to Jonah’s remarkable missionary journey to Gentiles.

The reason fish, seas, fishermen, and water crossings are everywhere in the New Testament has something to do with the changing nature of Israel’s mission. They are now to go out of the land and into the nations. Most of the gospels speak a lot of seas and sea crossing, where it might be more natural to speak of lakes, as if they mean to underline this theme. Luke, by contrast with the other gospels, does not speak of the ‘sea’, but of the ‘lake’. However, the emphasis shifts to seas and sea journeys in the book of Acts. Lakes are the ‘seas’ of the land, upon which the disciples train for the greater sea journeys that lie ahead of them. Peter will later go to the sea side town of Joppa, which is where he will be prepared for the mission to Gentiles (Acts 9-11).

From 4:38, we can see that Simon Peter and Jesus presumably knew each other already. Jesus wasn’t cold calling. What is going on in 5:1-11? Verses 9-10 suggest the events are, to some degree or other, to serve as a sign for the disciples. Jesus teaches from Simon’s boat put out from the land. A boat is a piece of land upon the waters, which is what the Church is. Jesus here symbolically represents the character of the Church’s future identity, mission, and success to his core three disciples.

The title of this section in my Bible is ‘Four Fishermen Called as Disciples’. However, the text only mentions three: Simon Peter, James, and John. People presume that Andrew was also present because of related accounts in Matthew and Mark. However, although his presence is implied within verses 4-6, he is an invisible presence, and the conversation between Jesus and Simon Peter proceeds as if they were the only significant people present. Jesus asks Simon to put out from land in verse 3 and instructs Simon to put down the nets in verse 5. Simon obeys in verse 5. It is as if only Jesus and Simon were in that boat, and James and John in the other. This may seem just an oddity, but there might be more to it.

As James Jordan has argued, a leader with three close supporters or friends is a pattern in Scripture. For instance, Abraham (Genesis 14:24); Moses (Exodus 24:1); David (2 Samuel 23:8-17); Job (Job 2:11—three supporters who failed him); Hezekiah (Isaiah 36); Daniel (Daniel 1:6-7); Jesus (Matthew 17:1); the Spirit and three ‘pillars’ (Galatians 2:9). The leader and his three are like cornerstones of society. This might be why Luke only focuses on Simon Peter, James, John, and Jesus. With Jesus, these three men will form the foundations of the new Israel.

Throughout this chapter, Jesus is forming a new Israel around himself. The leper (not the same as modern leprosy) would have been prevented from participating in worshipping community. The paralytic is in a similar position. He cannot get into the community, so has to be lowered through roof. Jesus forgives him, ‘raises him up’, and makes him one of community ‘glorifying God’.

As in the book of Galatians, table fellowship and food practices are crucial questions posed to Jesus (verses 27-39). In eating with tax collectors and sinners, Jesus is forming a new Israel, as Israel was defined by such things. By eating with sinners, Jesus is declaring them to be restored members of the true Israel and no longer outcasts. He is enacting Jubilee.

Jesus’ answer to Pharisees in verses 33-35 presents his meals with tax collectors and sinners as a sort of moveable wedding feast with himself as the bridegroom. The fasting John the Baptist was like the best man (cf. John 3:28-29).

In verse 35, Jesus is already alluding to his being taken away from his disciples.

Jesus brings new wine, something that cannot be contained in old structures. Jesus isn’t just patching up the old garment of Israel, but is making things new. The old way of being Israel cannot contain Jesus’ liberating kingdom. Verse 39 is perplexing, as it seems to run against the more general sense of the preceding verses. Perhaps Jesus is making a point about the instinctive conservative impulse of the Pharisees who have enjoyed the ‘old wine’. They presume that the old wine is better and that the best wine comes first (this interpretation could be filled out by comparison to John 2:10). However, the new wine that Jesus brings is the superior wine.

LUKE 6

Jesus’ actions upon the Sabbath were not technically against the Law. What they demonstrated, rather, was the priority of his mission over other considerations. Jesus’ argument is not that being nice is more important than following the Torah but is a claim about who he is relative to the Sabbath. Lest we forget, the Sabbath was a big identity marker for the Jews. People had died for this.

Jesus references 1 Samuel 21. The point that he is making isn’t ‘David broke the Law’, but rather that the status of David and his mission took precedence over ordinary priestly considerations. Note that in 1 Samuel David points to the holiness—not just the cleanness—of his men. For the period of their mission they were those with a status like that of priests (note that the Nazirite vow is associated with warfare at various points). In a related manner Jesus, as the bringer of true rest, takes precedence over the day of rest. He is its Lord.

Could the healing of the man with the withered hand be an allusion to 1 Kings 13:1-10?

Jesus goes to ‘the’ mountain to pray. The definite article is used several times in the gospels when referring to an unnamed mountain (just as it is within the Old Testament). What is the significance of ‘the mountain’?

Like other big transitions in the gospel, Jesus prays all night before choosing his disciples. Prayer is a significant theme in the gospel of Luke. Alone among the gospels, Luke speaks of Jesus praying immediately prior to his anointing by the Spirit at his baptism and at the moment of his transfiguration. The twelve disciples are the leaders of a new ‘twelve tribes’ of Israel.

The beatitudes should be read in the light of Old Testament prophecy. In Matthew’s gospel the beatitudes are alone in chapter 5, with corresponding woes in chapter 23 (they map onto each other: take a look). In Luke, by contrast, the beatitudes and the woes are side by side and the latter are the reverse of the former.

Jesus’ teaching breaks right through a culture of honour and shame, gift and debt. We are beyond shaming and can turn the other cheek. We can give to our enemies and those who can’t return because God is the guarantor of all gifts and debts.

As Peter Leithart observes, ‘sinners’ in Jesus’ teaching look a lot like Pharisees. Jesus is redefining the terms.

Jesus’ teaching about judgment, despite much modern misunderstanding, is not that we should never judge, but that we should always look to ourselves first, check our own ‘vision’, be alert to hypocrisy, and submit to the same judgment ourselves. Also, especially importantly, the giving of judgment is contextualized by the giving of bountiful gifts to others. We like to give our extravagant judgments to others, less so our lavish forgiveness.

We should not miss the shocking character of Jesus’ teaching about loving enemies and submitting to expropriation in the context of an occupied country.

Want to master your words and actions? Then guard your heart.

N.T. Wright suggests a temple reference in Jesus’ teaching about building the house. Israel was in the process of a massive temple-building project, but had built it without foundation. When the waters (of the Romans) arose against this house (cf. Isaiah 8:1-8; Luke 21:20-24), it would come crashing down, but temple of the Church built on Jesus’ words would stand.

LUKE 7

Jesus mentions Elisha and Naaman (2 Kings 5:1-14) and Elijah and the widow of Zarephath (1 Kings 17:8-24) in 4:25-27. The healing of the centurion’s servant (healing from a distance done for foreign military man) and the raising of the widow’s son are parallels of these events. Jesus is a new Elijah/Elisha.

The elders of the Jews present their case: ‘the centurion is worthy for you to do this, look what he has done for us’ (vv.4-5). The centurion’s assessment is strikingly different: ‘I am not even worthy for you to come beneath my roof, but you can do this.’ The centurion has far more faith than the Jewish elders. He knows Christ can heal from a distance, and knows he isn’t worthy. The Jewish elders still haven’t learned the lesson of 6:32-36.

John the Baptist is presumably expecting the judgment of fire that he announced that Jesus would bring. He didn’t expect that Jesus’ ministry would take the form that it does. Jesus enacts God’s gracious patience towards his people. In response to John the Baptist’s query, Jesus demonstrates his healing and reminds John of Isaiah’s prophecy (verse 22). John’s ministry obviously had deep significance for Jesus. He refers to John’s testimony on a number of occasions in the gospels.

‘Among those born of women’ is contrasted with ‘in the kingdom of God’—is Jesus implicitly contrasting two ‘births’ here?

The common people and tax collectors recognize the justice of God, but the Pharisees and lawyers reject God’s saving justice. They’re so out of sync with God’s justice they want to dance when they should be mourning, and to mourn when they should rejoice. They describe Jesus, the faithful Son, as a ‘glutton and drunkard’. Deuteronomy 21:20 is important background here: the wicked and rebellious son is put to death (the text immediately goes on to refer to hanging on a tree). Israel is actually the rebellious son, but Jesus is taking the judgment upon the nation. ‘Wisdom is justified by all her children’—the true children of God’s Spirit and Wisdom recognize and approach God’s justice.

Jesus is accused of eating with tax collectors and sinners. Next scene, he’s eating with a Pharisee. Touché.

Simon the Pharisee invites Jesus for a meal, but fails to provide some of the basics of expected hospitality. One is left with the impression Simon is trying to shame Jesus. The woman, realizing this, goes to Jesus and performs the most extravagant act of hospitality imaginable, performing far over and above anything that Simon has failed to perform. She goes to scandalous cultural extremes. We shouldn’t miss this. She looses her hair. She touches Jesus. She anoints and kisses his feet (actions which were more sexually weighted than they are today). She weeps openly. No ‘respectable’ woman would do any of these things (much like David’s actions in 2 Samuel 6). However, she loves Jesus too much to behave in a restrained fashion. She behaves towards Jesus in a way that one could only ever really imagine a wife behaving towards a husband. She recognizes that the Bridegroom has come to the feast. Simon, who completely fails to honour Jesus, does not.

LUKE 8

Jesus’ ministry was supported by faithful women, in much the same way as Elisha’s ministry was (cf. 2 Kings 4:8-11). These women also seem to have accompanied Jesus and his disciples as they travelled around. While the focus is usually upon the Twelve, Luke wants us to know that they were only some of a larger group.

The Old Testament prophets spoke in parables, which cryptically revealed God’s purposes. Jesus follows in their steps. Parables are not ‘illustrations’, but cryptic riddles, designed to hide prophetic mysteries from the unfaithful, yet reveal them to the remnant. Speaking in parables and riddles was a form of judgment upon a people without spiritual perception. The quotation of Isaiah 6:9 in verse 10 is very significant and potentially gesture towards a central theme. In Acts 28:26-28, this verse concludes and sums up Luke’s narrative.

The notion of ‘sowing’ is elsewhere associated with return from exile (e.g. Jeremiah 31:27). God will ‘sow’ his word and a new restored Israel will rise up (Isaiah 55:10-13). N.T. Wright suggests that the parable of the sower should be read as the climax and recapitulation of Israel’s story. Climax: it presents the history of Israel as a story of successive ‘sowings’ of differing success and duration, leading up to the great Kingdom Sowing, which Christ is undertaking in his day. Recapitulation: it presents all of these different responses to the word of God sowing a restored people as occurring within Jesus’ own ministry. Jesus’ ministry won’t meet with a universally positive response, but the word of the kingdom that resows a restored Israel will receive mixed responses.

Could the hundredfold increase be a subtle allusion to Isaac and his riches (Genesis 26:12)?

Is the lampstand a reference to the lampstand of the temple? The lampstand bears the light of the Spirit to light the world. It is like the burning bush. However, in the old covenant, the lampstand was hidden. At Pentecost the flame of the Spirit comes down and lights the Church as a living lampstand (note the connection between churches and lampstands in Revelation).

Jesus challenges the supposed claims of his natural family upon him. Just the Temple was his true Father’s house, so his true family are those who hear and obey his Father’s word.

We tend to read Jesus’ miracles as signs of his divinity, which is true. However, they are also signs of humanity enjoying the full dominion over the creation we were created to attain to. They are signs of God’s future for us thrown back into history.

There are echoes of Jonah and the Red Sea crossing in the story of the calming of winds and waves. Also notice the exorcism analogies.

René Girard has some perceptive comments on the story of the Gadarene man among the tombs here. The man among the tombs is the living dead. He is the scapegoat of his community, the one who bears all of their demons. When he is healed, it is crisis for the community, because they must face their own demons. The pigs are the unclean animals that represent the community. When the demons leave the man, the demons are revealed to belong to them. How often do we see situations where one member or group of persons in a family or community are made to bear all of the communities’ demons? If they are healed, it is a crisis, as people can no longer point the finger, but face their own demons.

Usually the crowd would cast the single victim over the cliff. Here the single victim is restored and the ‘crowd’ go over the cliff. Jesus reveals himself to be the master of the deep, not just stilling its winds and waves, but casting demons into the abyss.

The woman had a flow of blood; Jesus has a flow of power. Jesus raises the woman with the flow of blood from ceremonial death, enabling her to participate in Israel’s religious life again.

Jairus’ daughter is twelve years of age. The woman has suffered from the issue of blood for twelve years. These are two pictures of Israel. Jesus is raising the ‘daughter of Zion’ from exclusion and death to new life and fellowship (note that both Jairus’ daughter and the woman with the issue of blood are referred to as ‘daughter’).

‘Spent all her livelihood on physicians and could not be healed by any,’ wrote Luke, the physician.

The woman touched the tassel of Jesus’ garment. God commanded Israel to have blue tassels on the corner of their garments in Numbers 15:38-39. The threads are wool, more associated with garments of the priest. Every Israelite, as they are faithful to the covenant has, as it were, and as in garden of Eden, waters flowing out from them to give life to the world. Jesus’ healing of the woman who touched his tassel is a powerful fulfilment of this. Perhaps this is also connected with Ezekiel 16:6-9.

LUKE 9

We have seen a steady growth of the group around Jesus. It starts with core three in 5:1-11, then develops to the twelve in 6:12-16. In 10:1 there will be the seventy. Jesus is forming a new Israel around himself: three other cornerstones, twelve tribes, seventy elders. In commissioning the Twelve, Jesus emphasizes their dependence upon God’s provision. They don’t carry their own provisions.

I wrote a piece on Exodus themes in Luke 9:10-50 a while back. In feeding the five thousand Jesus is following the example of Elisha in 2 Kings 4:42-44. All of the gospels inform us that there were five loaves, two fish, and twelve baskets taken up. This suggests to me that the details are significant. I’ve already reflected upon the meaning of the twelve baskets in the post linked above: what about the five loaves and two fish?

At the outset, let’s pay attention to obvious: loaves are ‘landfood’ and fish are seafood. Fishing and fish are associated with the Gentiles. After his resurrection, Jesus eats fish and bread (Luke 24:42; John 21:13), which perhaps represents Israel and the nations.

Why five loaves? In 1 Samuel 21:1-6, David feeds his men in the wilderness with five loaves of the showbread. Notice that the seven loaves appear in the feeding of the four thousand in Matthew and Mark, making up twelve.

The reason why there are two fish is less clear to me (the feeding of the 4,000 is vague on the number of fish too). There were two fishing vessels in chapter 5. That might have something to do with it. But I am uncertain on that front.

The fact that Jesus’ prediction of his death and resurrection immediately follows Peter’s confession is not incidental, I think.

The reference to those standing there who won’t taste death before seeing the kingdom of God could be related to the Transfiguration but also points beyond, I believe, to the fuller realization of the mystery of God following the destruction of Jerusalem in AD70.

Jesus uses little children as paradigms of faith in his teaching on a number of occasions. This is worth reflecting upon.

The reference to the cross in verse 23 is the first in the gospel. Before anything is said about Jesus going to the cross, the disciples are told that they must take up their cross daily and follow. This image would have struck them with a particular force and Jesus’ going to the cross would probably have been understood at least in part in the light of it.

Peter wants to construct tabernacles or booths. However, the time for the Feast of Tabernacles has not yet arrived.

In verses 46-56, Jesus challenges a number of his disciples’ power issues. First, their desire to be greatest. Second, their desire to monopolize the market on Christ’s kingdom ministry. Third, their desire to wield destructive power against others.

Foxes have holes, birds of the air have nests. Is this a reference to Herod (13:32) and to the Gentile nations and rulers (Matthew 13:32)?

The final verses of chapter 9 seem to allude to the calling of Elisha by Elijah at the end of 1 Kings 19.

LUKE 10

Seventy—in some texts seventy-two—disciples are appointed and sent out. What to make of the number? Some observations: 1. There were seventy nations of world in Genesis 10, representing all of humanity; 2. Seventy persons came with Jacob into Egypt in Genesis 46:26-27. Jesus, the new Jacob, has twelve disciples as Jacob had twelve sons and seventy more in the wider body of his family; 3. There were seventy elders of Israel who received Moses’ Spirit in Numbers 11; 4. It could relate to the number in the Great Sanhedrin. The choosing and empowering of the seventy represents Christ’s formation of a new Israel and new polity.

Then what about the pesky two others, if the 72 text is correct? First, the 70 associations listed above would still generally pertain, albeit more loosely; Second, there were two extra in Numbers 11, Eldad and Medad. Third, 72=6×12. Luke has already used the numbers 77 (7×11) and 84 (7×12). The 12 would connect the number more closely with the tribes and with the Twelve.

The reference to the harvest might look back to the seed-sowing mentioned a few chapters earlier. Were the Twelve (9:1-6) sent as sowers, with the seventy as the reapers? There is a much greater emphasis upon judgment associated with the mission of the seventy, which might relate to this. They gather the wheat, but bring down judgment upon the chaff.

They are sent out as teams of two, which might recall the Flood. The sending of the Twelve and Seventy might also recall the spying out of Promised Land under Moses and Joshua (there are hints these went in pairs). These spies bring back a good report.

The connection between the reception of the seventy disciples and the final judgment reminds me of Matthew 25:31-46. Although readings of the parable of the sheep and the goats tends to focus upon our general attitude to people in need, this isn’t quite what the passage is about. The passage is about Jesus’ brethren, who aren’t the poor in general, but Jesus’ disciples (e.g. Matthew 12:47-49; 28:10). The way that the towns received Jesus’ seventy ‘brethren’ would weigh in their final fate.

Once again, in 10:17-20, the theme of heavenly conflict comes to the foreground. Jesus’ vision probably refers to something that hadn’t occurred (cf. Revelation 12), but which would result from events put in motion with the spying out of the land. The emphasis upon conflict with Satan and his demons makes clear that Israel is his occupied territory, not just Rome’s.

Verse 21 is a very Trinitarian verse.

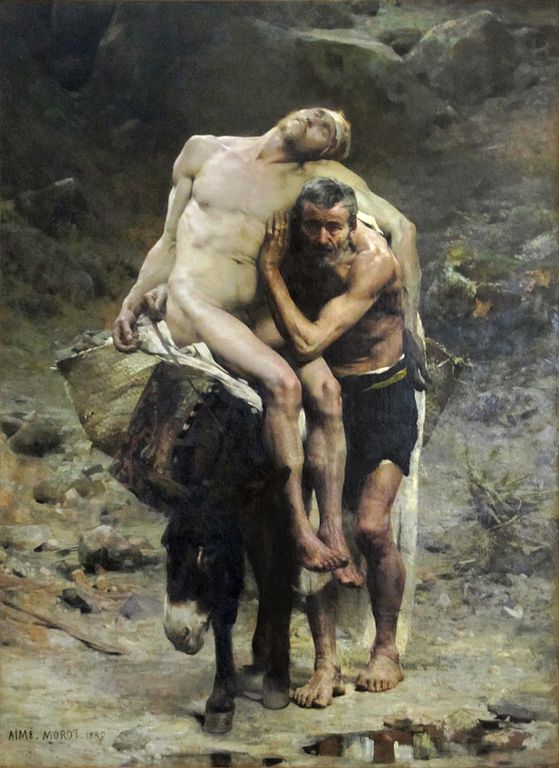

The parable of the Good Samaritan reminds me of the story of 2 Chronicles 28:9-15, especially verse 15. I’ve commented at length on the connection here. The Levite and the priest were men associated with the serving of the temple. They probably avoided the half-dead man in part because they feared being rendered unclean by touching a corpse and having to suspend their temple duties for a time. The religiously compromised Samaritan, by contrast, has compassion upon the half-dead man. He pours on oil and wine, treating the half-dead man as he would a sacrifice. His act of mercy is a truer sacrifice than the compassionless ceremonial purity of the other two men.

The lawyer wants to present himself as being in the right relative to the Torah and thus wants to limit the scope of its definition of neighbour. Jesus answers him by pointing to an act of neighbour-making, an act that does not constrain its moral concern to a carefully defined scope, but which goes out of its way to form new bonds. This is only possible for people who are not trying to justify themselves: an expansion of moral concern for anyone trying to justify themselves will only produce guilt. Jesus turns the lawyer’s question around: not ‘who is my neighbour?’ but—implicitly—‘are you a neighbour?’

Mary of Bethany is associated with Jesus’ feet almost every time we meet her (Luke 10:39; John 11:2, 32; 12:3).

Mary takes the place of learning before the rabbi, a place usually restricted to men. Mary and Martha is too often read in terms of the typical double-bind placed on women: the expectation to serve accompanied by the judgment that they should be ‘more like Mary’. This, however, is not really the point. The story needs to be read with the parable that precedes it. Both are shaped by theme of inheritance: the lawyer wants to know what to do to inherit, while Mary has chosen the ‘good portion’ (cf. Psalm 16:5-6). Like priest and Levite, Martha is preoccupied with offering ‘bread’. The Samaritan appreciates that compassion is more important than sacrifice and Mary that the One who dwells in the temple is greater than the service of that temple. Martha, like many in the gospels, judges Jesus’ followers for failure of expected service, while missing the fact that God has visited his people and that he must take priority.

LUKE 11

Luke emphasizes prayer to a degree that the other gospels don’t. Notice, for instance, that Jesus prays before the heavens are opened in his baptism (3:21) and before he is transfigured (9:29). This isn’t recorded in the other gospels. Jesus also prays before all big developments in his ministry. Seeing the importance and power prayer had for Jesus, it is natural that the disciples would want to learn how to pray from him.

The Lord’s Prayer isn’t just a worked example of a good prayer, although it is that: we should pray with these particular words.

The Lord’s Prayer has the rough pattern of the Ten Commandments. It begins by identifying one God (commandment 1). It addresses him in heaven, implicitly ruling out all idols (commandment 2). It proclaims the hallowedness of his name (commandment 3). It seeks the coming of his Sabbath kingdom (commandment 4). It seeks for forgiveness for sins by referencing our addressing of our wrongs against our neighbour (commandments 5-9). It seeks for deliverance from temptation (commandment 10). In this chapter, Jesus will go on to address the mere outward observance of the Torah, versus the obedience of the Torah from the cleansed inside. It seems to me that the Lord’s Prayer and prayer in general is integral to Jesus’ teaching about this mode of obedience. The true Torah-observance that God seeks begins and ends in the act of prayer.

Notice that the example of prayer in verses 5-8 is of prayer in order to have something to give to others. Our heavenly Father will give the Spirit to those who ask him. Prayer preceded Jesus’ reception of the Spirit and also Pentecost.

The people accuse Jesus of acting by the power of Beelzebub. But they are the ones ‘testing’ him, just as Satan had done. ‘If I cast out demons with the finger of God…’—Note the parallel with Exodus 8:19. Jesus implicitly compares those testing him with Pharaoh’s magicians in the Exodus account. Jesus presents the situation in terms of the Exodus. He is delivering an enslaved people from Pharaoh/Beelzebub by the finger of God.

Verse 23 should be compared to 11:49-50. People who are ‘not against’ the disciples are for them. However, with Jesus himself, you are either expressly for or against him. There is not ‘not against’ middle ground.

Cleansing isn’t enough. It just makes us neutral and we can be overtaken by worse sins. We must be filled by the Holy Spirit.

‘Blessed is the womb that bore You’ … ‘More than that, blessed are those who hear the word of God and keep it.’ The blessing of Mary is not on account of the mere physical bearing of Jesus, but because she believed the word of God (1:45). Mary is the first and paradigmatic new covenant believer.

The sign of Jonah is the sign of Jesus’ death and resurrection but also of the fact that the Gentiles will be more responsive. Both dimensions of the Jonah story, but particularly the latter play into its typological importance in this context.

It is the eye that allows light to enter the body. If your ‘eyes’ are good and you can truly perceive the kingdom, your life will be filled with light. Notice that that which gives light to the body is not something that we create within ourselves: rather, it is a mode of perception of something outside of us that shapes us. As our eyes perceive Christ by faith our whole lives will be filled with his light.

The judgment upon that generation was the accumulated judgment due to the first to the last Old Testament martyrdoms (verse 51).

As hidden graves (verse 44), the scribes and Pharisees spread uncleanness to others without the others realizing. Throughout these verses, Jesus highlights the damage that unfaithful religious leaders spread to those around them and the immense judgment that they face.

Lawyers in v.45: ‘Be careful, some of your stray bullets are hitting us!’ Jesus in v.46: ‘Watch me take direct aim!’

LUKE 12

‘Beware the leaven of the Pharisees.’ Once again, Exodus themes are surfacing. In leaving Egypt the Israelites had to purge out its leaven in the Feast of Unleavened Bread. The leaven—the old life principle—associated with the Pharisees’ teaching, must be removed for all associated with the Exodus that Jesus was going to accomplish in Jerusalem.

Concealed things will be revealed and hidden things will be made known. The confession of Christ before men will be proclaimed in the heavens. The denial of Christ before men will lead to denial before the angels of God. Leaven is ‘hidden’ within loaves (cf. 13:21), but its effects become very visible over time. This is a powerful illustration of the hypocrisy of the Pharisees. It may not be easy to see at first and its workings are hard to uncover, but its effects are huge over time and affect the whole. The same is true of the leaven of the Holy Spirit. A similar pattern can be seen in families and churches. The background spiritual atmosphere of such contexts functions like the hidden working of leaven. Beware of hypocrisy.

Five sparrows are sold for two copper coins. Five loaves and two fish. Any reason why these numbers appear together?

What is the unforgivable sin of blasphemy against the Holy Spirit? Jesus is speaking of two stages in his ministry, a theme that Stephen later takes up in his sermon in Acts. Jesus’ first coming will end in rejection and death. However, Israel will be forgiven if they respond to ministry of the Holy Spirit through the Church. If they rejected that too, no forgiveness remained for them, just certainty of judgment.

Jesus does not take on the role of judge (v.14). Judgment will be delivered to him at the ascension. Notice the parallel between Jesus’ statement in verse 14 and the pointed question addressed to Moses in Exodus 2:14. The man wants to divide the inheritance, rather than sharing it with his brother in unity, and will go to law against him. This is why Jesus tells a parable about covetousness and greed. The man values the inheritance over his brother.

Verses 22-34 should be read and re-read. We fret and worry, but it is God’s good pleasure to give us the kingdom.

‘Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.’ If you want your heart to be in Jesus’ service, invest in his work.

Verse 37 is an astounding picture. The master who finds his servants waiting for him will gird himself, set them down at his table and serve them with his food. The entire order is turned upside-down.

‘Life is more than food, and the body is more than clothing.’

Beating fellow servants is persecution of the people of God.

Jesus’ description of his death as a ‘baptism’ is striking and provides a background for idea of baptism into Christ’s death.

Verses 49-53 harken back to the themes of John the Baptist’s teaching.

The coming crisis will cut right through family relations. ‘Family values’ will never be comfortably underwritten by the kingdom.

Jesus calls his hearers to make every attempt to settle with their adversary before being brought to judgment. This refers both to giving up their doomed opposition to Rome, and, more importantly, to getting right with God before his judgment falls.

LUKE 13

‘You will all likewise perish’—as N.T. Wright argues, Jesus is probably referring to the literal judgment coming upon Jerusalem in AD70, with falling masonry and a sanguinary catastrophe that will fall upon the nation, its temple, and sacrificial system.

Jesus mentions 18 people killed in verse 4, then 18 years of infirmity for the woman in verses 11 and 16. I am unsure of the significance of this particular unusual number, but at the very least it serves to connect the two stories together. Again, the number three occurs a number of times in this passage (vv.7, 21, 32).

Elsewhere in the gospels the fig tree serves more explicitly as a symbol for the nation of Israel. Jesus is the patient keeper of the vineyard, seeking to delay judgment upon the nation and its temple.

Jesus seems to make a point of healing upon the Sabbath. He brings in the true Sabbath rest of the kingdom to Israel. The Sabbath healing of 13:10-17 should be read alongside the Sabbath healing of 14:1-6. They have much in common.

The mustard seed is later used as an image of faith (17:6). The mustard seed becomes a ‘great tree’. However, in real life it doesn’t: it just becomes a modest bush. This is part of the point of the parable, I suspect. Whatever size the kingdom appears to be, this is its actual significance.

The leaven may be an image of the people of God, hidden within the three loaves of humanity (Shem, Ham, and Japheth). We may not be seen, but God will accomplish a hidden work through us that nonetheless has very visible effects.

Jesus’ teaching regarding the fewness of people to be saved probably shouldn’t be taken as a general statement about all of history, but as a particular word addressed to his own generation. He speaks of people coming from all over the world.

In verses 32-33, Jesus describes his work in a symbolic three day pattern, corresponding to pattern of death and resurrection.

Jerusalem is the site where the prophets’ blood must be gathered. Is the blood of the prophets scattered in the holy city to be related to the blood of the sacrifices poured out in the temple? The house—the temple and, by extension, the whole nation—is to be left desolate.

Jesus wants to gather Israel under his ‘wings’, a biblical image of God’s protection and provision of refuge for his people. Jesus compares himself to a hen immediately after speaking of Herod as a fox. This is probably not a coincidence.

LUKE 14

Luke 14 is set at the meal table. The kingdom is like a great supper and the way of the kingdom is seen in its ‘table manners’.

Jesus heals on the Sabbath again. Notice the parallels with 13:10-17. He is bringing in the Sabbath rest and feast. The man is suffering from dropsy, a condition involving fluid retention and a dangerous thirst. Jesus heals him and thereby addresses his thirst, a symbol of longing for deliverance in exile.

The meal table is where dynamics of honour and shame are most potently expressed. Seating arrangements and dinner invitations are means for social climbers to accrue honour and status among men in an honour/shame society. Jesus challenges this by calling his disciples to reject the way of honour-seekers and, like their Master, to despise the shame. As we humble ourselves before men, God will raise us up.

An implied teaching in these verses is God is the guarantor of all gifts and debts. No gift that we give will go unrewarded and if we give by faith to the poor, we will receive a bountiful reward at the resurrection. Conversely, we need not be placed in others’ debt when we receive their gifts, because God has promised to repay them on our behalf. The significance of such teaching in a society of gift and debt is absolutely immense and seldom truly appreciated.

Jesus tells us to invite the poor, maimed, lame, and blind to our suppers, rather than people who can repay us. God is the one who will reward us with a place at his table in the resurrection of the just. How seriously do we take Jesus’ teaching here? I think that Jesus meant us to take this quite literally.

Jesus’ meals were a symbolic means by which he was reforming Israel around himself. Those who rejected Jesus would find themselves outside of the eschatological feast, while the poor and the outcasts celebrated within.

We must count the cost if we want to be Jesus’ disciple. We tend to present being a disciple in the most positive of terms, suggesting that it will make people’s lives wonderful. By contrast, Jesus presents discipleship as deeply demanding and alerts us to how hard it is. We try to ‘sell’ discipleship like a product, while Jesus challenges prospective disciples to demonstrate their level of commitment to him. If anyone, Jesus is in the position of the buyer in the transaction. It seems to me that we haven’t reflected half enough on the significance of these verses when it comes to Christian evangelism.

‘Salt is good.’ The reference to salt probably has to do with the sacrifices (Leviticus 2:13). The people of God are to be the seasoning on the sacrifice of the world, giving it its savour to God.

LUKE 15

As we read these parables, it is important to keep in mind that they are addressed to the Pharisees and the scribes (vv.2-3).

These three parables need to be read together. They each develop a single theme in a different way and the contrasts and progression between them matter.

The first parable is about a shepherd. Jesus is the Good Shepherd, but is addressing false shepherds of Israel (cf. Jeremiah 23; Ezekiel 34). It seems to me that the shepherd here is not God, but the ideal leader and teacher of Israel. The parable reveals the sin of the scribes and Pharisees, as they destroyed, scattered, and fleeced the flock of Israel and did not seek the lost. The finding of the lost sheep leads to a feast of celebration, whose joy reflects the joy of heaven itself (v.7). Jesus’ meals with tax collectors and sinners enact this celebration of the discovery of the lost. Not only are the Pharisees and scribes failing to seek the lost sheep of Israel, they also lock themselves out of the joyful feast of celebration. The recovery of the lost sheep might remind us of the idea of the Lord’s ‘restoring the soul’ of the psalmist in Psalm 23:3.

The parable of the lost coin is the second parable in the cycle. The woman had ten coins, in what was most likely a bridal garland or dowry, from which she had lost one. This was a serious thing to lose. The coin was a mark of the woman’s marital status. Who is the woman? It seems to me that the woman is most likely Israel. The implication is that recovered lost sinners of the house of Israel are akin to the marks of Israel’s status as God’s bride.

The house imagery might also be worth reflecting upon. We have already read of a swept house (11:25) in relation to casting out Satan. We have also seen a number of references to lamps (11:33-36; 12:35). There might be some allusion to the temple here. Jesus is a true son of the Bride, sweeping out Satan from the house, relighting the lamp of Israel, and recovering the marks of Israel’s marital status by recovering lost sinners. He makes the unswept and dark house of Israel the site of a joyous feast. By contrast, the scribes and Pharisees are leaving the house dark, unswept of Satan, and are losing the marks of marriage.

The final parable in the cycle is of the lost son. Notice the movement: 1 of 100 sheep lost. 1 of 10 coins lost. 1 of 2 sons lost. The wave of anticipation should be rising. In the older brother figure, it makes explicit what is implicit in the others.

If I am correct, there is a movement in the parables from the ideal leader or teacher of Israel (the shepherd), to Israel herself (the woman with the coins), to Abraham or God (the father). The Pharisees and scribes are shown to be acting contrary to each of these, demonstrating that they are not truly of Israel at all.

The identity of the father in the parable could be God, as God’s fatherhood has been a theme in the book of Luke. However, a good case can be made that the father is actually Abraham. Abraham’s fatherhood, the identity of his children, and his centrality in the eschatological feast of restoration is a running theme in the book of Luke (1:55, 73; 3:8; 13:16, 28; 16:23-30; 19:9). Also, as the two sons recall characters in the book of Genesis, the father could fairly naturally be associated with their patriarchal father.

The younger son is in exile, in a ‘far country’ among the unclean swine. A number of people identify the younger son as Jacob, but I don’t believe that this is correct (even though the story plays off the Jacob story). Jacob is a righteous son who flees on account of the threat of his older brother, while here the younger son is Israel the nation who are a poor parody of their forefather, wilfully choosing the way of exile.

‘My son was dead and is alive again’—Resurrection!

The son expects a begrudging greeting, but finds his father running towards him and arranging a huge celebration in his honour.

There may be a development here too: ‘joy in heaven’ (v.7), ‘joy in the presence of the angels of God (v.10), God’s own joy (vv.20-24).

While it was famine or threat that typically led Israel away from the land, here it leads them back.

Everything is topsy-turvy in this parable relative to the story of Jacob and Esau. Israel hasn’t followed the script. Notice the greeting of the father (v.20) is precisely the same as the greeting given by Esau to the returning Jacob (Genesis 33:4). However, the older brother in this story will shut himself out of the feast, rather than welcome his returning brother. The older brother is clearly the Pharisees and scribes, who can’t even live up to the example of Esau. The younger brother seeks to return as a slave and is welcomed as a son. The older brother appeared to be a son, but all the time was thinking of himself as a slave and was seething with resentment and bitterness (v.29). The end of the parable leaves things hanging and unresolved (the end of Jonah is another example of this). The resolution must take place within the actions of the hearers of the parable.

Just as there is an inversion of the role of Jacob and Esau, there might be another inversion here too. I’ve wondered before whether Jesus was playing on themes of Exodus 32 here: like Moses, the older brother returns to hear the sound of music and dancing, wondering what is taking place. There is also a calf involved. The Pharisees and scribes feel anger like Moses. However, their anger is at the scandal of God’s grace in restoring such an idolatrous nation. Jesus alludes to Israel’s past unfaithfulness in his description of the mode of God’s welcome extended to them upon their return.

In sum, these three parables speak of the value of those who have been lost, the need to go to lengths to find them, the incredible joy at their return, and the tragedy and loss in locking oneself out of this joy on account of one’s resentment.

LUKE 16

The parables in Luke 16 are some of the trickiest of all. There is much here to reward closer attention, though.

Jesus is still speaking in the context set by 15:1-2 and will be doing so until 17:10. While he addresses his disciples (v.1), the Pharisees are also listening in (v.14).

In the parable of the unjust steward it is important to keep in mind that Jesus is praising his shrewdness, not his morality. The steward would have managed his master’s estate in his absence, sorting out rents and the like. Reference to ‘squandering’ might suggest some connection with the parable of the lost son that preceded it. The steward hasn’t been faithful to his master and faces imminent removal from his position. It is crisis time. What is he to do?

The steward comes up with an ingenious scheme. While he is about to lose his position, apart from his mater no one else yet knows this. He goes around all of his master’s debtors and reduces their debts. This would make him a hero in the neighbourhood and his master would appear to be generous and good. The master now couldn’t easily remove him from his position or recover full debts without appearing grasping and courting public disfavour. Even if removed from his position, the steward would be welcomed by people in the neighbourhood. The steward was accused of wasting his master’s goods. There is also a distinct possibility that he was raising the rents. The reduced debts were probably largely taken from his unjust cut. He had been placing heavy burdens on people.

So, what is the point of the parable? The Pharisees and scribes are unjust stewards. They have been squandering God’s riches and laying heavy burdens upon his people. The time for their accounting to their master has come. They are now faced with a choice: will they double down on their injustice, or will they use the brief remaining period of their stewardship to take emergency action to prepare for the future?

The action that Jesus implies they should take is that of getting on the right side of their master’s servants and debtors before it is too late. The servants and debtors are the common people they had been mistreating. If they reduced their burdens and made friends with the poor, the poor might welcome them into the eternal habitations of the kingdom (the theme of making peace with the poor for the sake of a future part in the kingdom might also be alluded to in the rich man’s address to Lazarus).

Of course, unlike the shrewd steward, the Pharisees, scribes, and lawyers were oblivious to their predicament and remained unjust. The scribes and Pharisees have not been faithful with the old covenant ‘least’: God will not entrust them with new covenant riches. Jesus is clearly accusing the Mammon-serving Pharisees of abusing their power for the sake of dishonest gain from the poor. There is a change in the world order afoot and people are pressing into the kingdom. The Pharisees must hurry or be left out.

Why the reference to divorce? It seems to me that the implication is that the religious leaders were abusing their role as the guardians of the law to exploit poor and gain wealth, but also to loosen standards of marital unfaithfulness and sexual sin in their favour. Important background here is book of Malachi, which speaks about such unjust religious leaders and highlights divorce (2:14-16).

I think that N.T. Wright is correct in his claim that the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus is not about the post-mortem state (just as the parable of the Sower is not primarily about sowing but about the proclamation of the kingdom). Rather, its description of the post-mortem state is a parable of something else.

The rich man clothed in purple and fine linen is an image of priesthood (cf. Exodus 39:1ff.), Lazarus is like the leprous outcast. The ‘deaths’ of the rich man and Lazarus most likely refer to the end of the old order and the bringing in of the kingdom. Lazarus is now welcomed and the rich man finds himself excluded and seeking the mercy of the poor man. The rich man, finally appreciating what is taking place, begs for Lazarus to be resurrected to warn his ‘brothers’.

Jesus makes clear that the ‘brothers’—scribes and Pharisees—don’t know what is taking place before their eyes. Even someone rising from dead won’t change this (as his own resurrection will prove). They haven’t heeded Moses and the prophets; they won’t respond to kingdom resurrection. There is a stark image here. The rich man (symbolizing the priesthood), will be cast out in torment, while Abraham welcomes the poor Lazarus as his child. The lines of the family of Abraham are being redrawn in surprising ways.

See other #Luke2Acts posts here.