Symbol and Sacrament Posts: Introduction, Chapter 1, Chapter 2:I, Chapter 2:II, Chapter 3, Chapter 4:I, Chapter 4:II, Chapter 5, Chapter 7

Having established a model for the structure of Christian identity in the previous chapter, Chauvet proceeds to explore the interrelationships of the various elements of the structure. Within this chapter he examines the manner in which the Scripture grows out of the liturgy of Israel and the early churches, finds its place within the liturgy, the sacramentality of Scripture, and the manner in which Scripture ‘opens up sacramentality from the inside’.

The Bible Born of the Liturgy

The Jewish Bible and the Liturgy

Chauvet claims that the earliest patriarchal traditions were transmitted and collected in the context of cultic centres. The texts that we have were in large part conserved on account of their use in the liturgy: the biblical corpus is formed ‘in connection with a communal proclamation and listening’ (192). He quotes Paul Beauchamp’s formulation approvingly: ‘That is canonical which receives authority from public reading.’

The ‘great founding events of Israel (precisely because and to the extent they are recognized as foundational) are presented to us in the Bible through liturgical recitations.’ For instance, passages such as Exodus 12:1-13:16 are presented less as straight historical accounts than as guidelines for future liturgical memorialization, a fact that shows the great significant of the events. Something similar can be recognized in many of the passages in Exodus. ‘The authentic point of departure for the story is the celebrating assembly in its present reality’ (193).

[T]he great foundational moments of Israelite identity are recounted in liturgical terms. If the liturgy is not apparent in the text itself, it is because it is its pre-text. One does not tell the liturgy; one liturgically tells the story that one memorializes. The “liturgification” of the telling of stories about the early times is the best way to manifest their continuing foundational role in the identity of Israel. (194)

Chauvet also draws attention to the covenantal liturgies that appear at key junctures in Israel’s history, suggesting these were archetypal. These covenantal liturgies would have lesser analogues performed at various points in Israel’s life. These liturgies reveal ‘the essential dimension of the Bible, which is the confession of faith in Yahweh and, through this mediation, the very identity of Israel.’

None of this is to claim that the liturgy produced the traditions itself but that ‘it left its imprint upon them and played a decisive role in their being preserved as the “Word of God”’ (195).

The Christian Bible and the Liturgy

‘The Christian Bible is nothing else than a rereading of the Hebrew Bible in the light of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, of the rereading of these as accomplished “according to the Scriptures.”’ Chauvet argues that the oral context of the liturgy and the synagogue is crucial for understanding the way that texts, scriptural and otherwise, functioned within the early Church. ‘The Christian assemblies, Eucharistic and baptismal, seem to have functioned empirically as the decisive crucible where the Christian Bible was formed’ (197).

This can especially be seen in something such as the Last Supper accounts which presented themselves as historical narratives, but actually what they ‘narrate directly is the way the Church re-enacts the last meal of the Lord’ (198). The liturgical assembly is the source of these accounts. The fact that we have the Gospels in the form that we do results from the fact that the stories that they narrate were not merely of some departed beloved teacher, but of a living Saviour, and not of a tragic death of a leader, but of a death for us. This faith found its primary context in the liturgy.

It was the confession of faith in act in liturgical practice that ‘seems to have functioned as the catalyst allowing the different factors (doctrinal, apologetic, moral, liturgical) and the diverse agents (the Christian communities themselves with their concrete problems, internal and external; their various ministries of government, prophecy, teaching, prayer, and so forth) to come together in order to flesh out little by little these Gospels confessed as the gospel of the Lord Jesus’ (200). As in the case of the Jewish Bible, it was the authority recognized from public reading that provided the basis for the determination of canonicity.

The Place of Scripture in the Liturgical Assembly

Chauvet distinguishes between ‘canon 1’ and ‘canon 2’. Canon 1 denotes the ‘corpus, first oral, then written, which already functions as a practical canon of the traditions in which a clan, a tribe, or a group of people recognize and identify themselves’ (201). ‘In its final form, this canon 1 corresponds to the canonical Bible.’ Canon 2 is the instituting tradition, which ‘designates the hermeneutical process of rereading-rewriting canon 1 in relation to constantly changing historical situations.’ There is a ‘pheno-text’ (the apparent text of canon 1) that is ‘woven secretly’ by a hermeneutical ‘geno-text’ (‘hidden and creative text, canon 2’), a hermeneutical process that although unwritten, is obviously canonical (202).

The relationship between the instituted and the instituting tradition ‘depends on a third element: the events recognized as foundational.’ The confession is founded upon a narrative (our Christian creed is also a narrative embodying a theology). In many respects the Hextateuch can be regarded as the ‘theological unfolding’, the ‘transcription into capital letters’ of the events confessed as foundational (203).

The Law is first of all about stories, because these narratives from the ‘proto-historical period that the Torah covers act as the law for the identity of Israel.’

[T]he frontier of the Jordan and the death of Moses have a metaphorical significance: they separate irreversibly the historical types of the proto-historic period from all the future history of Israel. By this metaphorical separation, they are lifted out of their status as simply ancient events and promoted into meta-historical archetypes of Israel’s identity in the future. The original proto-history becomes thereby origin-giving meta-history, that is to say, always contemporary. Thus, for Israel, to live is to relive the journey of its origin by replunging itself into these memories again and again with each generation.

The same thing applies to Christians, the difference being that the ‘barrier’ that separates later history from proto-history is the resurrection of Christ.

The Book and the Social Body

Taking aim at classical theories of interpretation, and employing the work of Roland Barthes, Chauvet argues that every text is written and read from a particular world, rather than from ‘a neutral place that sovereignly transcends all socio-historical determinations’ (205).

Everything is interpretation. This does not mean that all interpretations are equal; a reading which can handle more aspects of the textual material is more faithful than another.

Chauvet distinguishes between decoding and reading.

Decoding is a technique of analysis, whether it be historical-critical, semiotic, or “materialist” … As necessary as decoding is for the reading to be faithful to the text, such a decoding is only a preliminary step in the service of the reading, for reading is the symbolic act of producing a new text, an original word, on the basis of the rules of the game decoded from the texts.

In reading, the reader and his world are engaged and they speak, which leads to the same text inspiring different readings. The decoding of the meaning of, say, a Shakespearean play is only the first step: the main task is found in creation of a new performance in which the Shakespearean text engages the interpreters and their world. On such an approach, meaning cannot be mastered. Rather we must submit to the ‘difference’.

The text comes into existence through the departure of its writer – the death of the author – becoming other to him, and being delivered over to the readers as a testament. The operation of reading is ‘essential to [the text’s] very constitution’ (206). Although we are inclined to think in terms of reading having to adapt to a normative writing, Chauvet suggests that we reverse this relation: reading ‘prescribes to meanings the general guidelines which they can and must follow’ (207).

We can draw distinctions between two different kinds of books, with many levels of gradation between them. On the one hand, there are ‘books requiring hermeneutics’, such as books of literature, religion, poetry, and philosophy. On the other hand, there are books concerned with disciplines of knowledge, such as scientific texts. The operation of the sort of reading that we have been discussing is far more noticeable in the case of the former than in the case of the latter.

Chauvet speaks of different levels of canonicity: ‘the more the social body recognizes itself in a text, the more the text manifests its essence as a text, in the sense explained above’ (207). There is the level of implicit canonicity that great literary texts can achieve, or that a work can enter for a time through winning a prestigious prize, or being the focus of an intellectual or cultural fashion. After this comes an intermediate level of canonicity, when a text surrounds itself with various normative interpretations (readings not always in agreement) as it is taught or discussed in academia, for instance (Plato is an example of this). The third level of canonicity, now completely explicit, occurs ‘when a corpus of texts is officially the subject of a global orthodox interpretation’ (208). ‘This canonicity is linked to the fact that the social body recognizes itself, consciously or not, officially or not, in the texts.’

In availing ourselves of J. Kristeva’s distinction between “geno-text” and “pheno-text”, we may say that the definitive setting of the canon of “holy books” is the ultimate unfolding, at the level of the pheno-text, of a process of canonicity constitutive of the geno-text, a process which manifests the essential relation of the reading body to the text.

For Chauvet, the book and the community are inseparable:

The norm is thus not the Book alone, but the Book in the hand of the community. The Church thus represents the impossibility of sola scriptura. (209)

It is from the encounter between the text and the reader that meaning arises. ‘Hermeneutics, although unwritten, is also canonical.’ This hermeneutical process of re-reading the Scripture in our world, of ‘drawing something new out of the old’ demands faithfulness in our situation to ‘the same process that brought about its production’ (the geno-text).

The Bible is formed through the process of selection among texts and in the process of integration, whereby ‘all parts of the book eventually converge toward the unity that is Christ’ (210). Chauvet concludes that ‘the Bible exists, as the Bible, only in the hands of the ecclesia.’ This does not mean that the Church is justified however it treats the Bible:

For our canon 2 has meaning only in relation to canon 1. And the Church itself has not always been faithful in its interpretation of the meaning of the data of canon 1 to which it necessarily referred itself…

The Reading of the Bible in the Liturgy

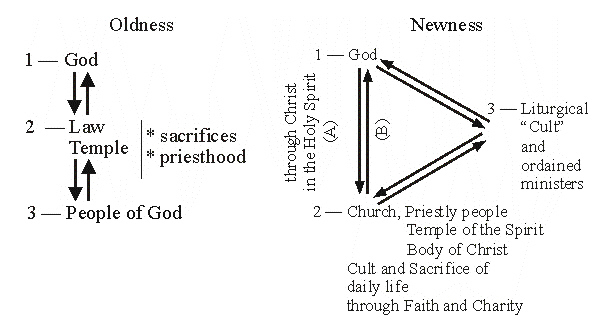

There is a relationship between four elements in the Liturgy of the Word. First, ‘texts are read from the canonically received Bible.’ Second, these texts are proclaimed as the Word of God for today. The writing of the text and the voice whereby it is read aloud place limits upon each other: we cannot recapture the origin, but there also remains ‘more to be written’ in the present (211). Third, the texts are read to an assembly that ‘recognizes in them the exemplar of its identity.’ Finally, this process is lead by an ordained minister ‘who exercises the symbolic function of a guarantor of this exemplarity and, for us Christians, of the apostolicity of what is read.’

These four elements correspond to the ‘four constitutive elements of the biblical text as the Word of God’. The first element corresponds to canon 1. The second element corresponds to the hermeneutical process of canon 2. The third element relates to the agency of the reading community that ‘writes itself into the book that it is reading’ (212). The final element relates to the manner in which ‘this dynamic internal to writing renders itself visible in the institutional act of canonical sanction uttered by an authority recognized as legitimate by the group.’

Thus, the complex formed by the four elements of the Liturgy of the Word may be understood as the visible, “sacramental” manifestation of the complex formed by the four elements which went together in the production of the Bible. So true is this that the liturgical proclamation of the Scriptures is the symbolic epiphany, the sacramental unveiling, of their internal constituents.

The essence of the Bible is unveiled in the liturgical proclamation. It is at that point that the writing of the testament, the living voice, the community of persons, and the representation of divine authority in the Church’s ministry come together. The Bible is never so much what it is than it is in the context of the liturgy: ‘the liturgical assembly (the ecclesia in its primary sense) is the place where the Bible becomes the Bible.’

The Sacramentality of Scripture

Many are inclined to regard the public reading of Scripture as merely one way among many whereby the Scriptures create the Church and the believing subject. However, Chauvet’s contention is that this activity is one of a different order from others, and should not be grouped with them.

Chauvet refers to the traditional veneration of Bibles, veneration comparable to that directed at the Eucharistic elements. Beautifully decorated lectionaries, the procession of the text into the Church with candles, incense, and singing, and other such elements serve as the ‘concrete mediation where the theology of Scripture as the sacramental temple of the Word of God is embodied’ (214).

The letter of the closed canon is the ‘tabernacle’ of the Word of God. In order to discover the Spirit and sacramentality of the Word we must engage fully with the text as letter. The Bible resists all attempts to distil it to a ‘timeless truth’ that escapes its historical contingency. Such an approach presumes that the Spirit must be located outside of the particularity of the letter.

There is a constant tendency to ‘blunt the letter’s resistance as the indication of an irreducible socio-historical otherness’ (215). This can be seen in certain forms of typology that do not accord to the letter the primacy that it deserves, or recognize the resistance that it poses. The ‘vertical model of metaphysics’ can be projected ‘onto the historical axis of time’.

Chauvet discusses the possibility of an idolatrous attitude developing towards the ‘letter-as-sacrament’ (216). He follows Jean-Luc Marion in defining idolatry, not as the ignorant identification of a god with its image, but in ‘the subordination of the god to the human conditions for experiencing the divine.’ Under this definition, it can be seen that idolatry can exist in a potent form even in belief systems that are supposedly anti-idolatrous. He lists the examples of conceptual idolatry’s reduction God to our closed discourses, ethical idolatry’s attempt to have rights over God on account of one’s behaviour, and psychological idolatry’s reduction of God to our ‘spiritual experiences’. All of these are attempts to put God at our disposal. ‘This is precisely the process of idolatry: to attempt to blot out the difference between God and ourselves’ (217). Thus, the letter becomes an idol whenever its difference from us is denied, and the immediate present and its prejudices become that to which the text is subordinated.

The icon contrasts with the idol by the separation that exists between its representation of the divine and the divine itself. There is only one small step from an icon to an idol, yet ‘this short step spans an abyss’ (218). The letter is sacramental ‘from an iconic perspective’. The sacramental character of the text is seen in its forming of figures.

[T]he letter arises as figure – and thus as a sacramental mediation of revelation – only by splitting itself in two: a witness to the “has been” of the creation, the Exodus, or the manna, it is at the same time a witness to the “must be” of a new creation, a new exodus, a new manna, and so forth. As figure, it is an in-between, a passage, a transit toward something other than itself, something else which is the other side of itself.

The Word of God always ‘resists any gnostic claim to a full presence’ (219). The ‘present’ of the Word of God is one that preserves radical otherness, difference, and separation.

The Sacraments as the Precipitate of the Scriptures

The sacraments are received from a tradition that we cannot manipulate at will, which precedes us, and which holds authority over the assembly and its members. ‘To the resistance of the letter, the rites add that of the body; the letter-as-sacrament precipitates itself into the body-as-sacrament in the expressive mediations of the rites: gestures, postures, objects, times and places, people with different roles…’ (220).

The ‘sacramental moment is preceded by a scriptural moment.’ This holds in the case of evangelization, where sacramentalization of persons follows after their evangelization, and allows this preceding evangelization to ‘take hold’, as we see in the Emmaus narrative. In this sense ‘the liturgical and sacramental expressions of the faith are a constitutive dimension of evangelization itself’ (221). The Word thus ‘deposits itself in the sacramental ritual as well as in the Bible,’ suggesting that an opposition or dichotomy between Word and Sacrament is false and misleading. What we have is the liturgy of the single Word in two modes, which are inseparably connected.

The Word of God shows resistance: it can be ‘difficult to swallow’. Chauvet uses John 6 to illustrate his point. The bread of life discourse is primarily a ‘catechesis on faith in Jesus as the Word of God’ (225). However, this catechesis on faith ‘is expressed in Eucharistic language, characterized as it is from start to finish by the theme of eating.’ The chewing of the Eucharist ‘provides John with a privileged symbolic experience of what faith is all about.’ It is always as Word that Christ gives himself to be assimilated in the Eucharist, which is why the preceding Liturgy of the Word is so important, as it enables ‘spiritual chewing’ in the sacrament. For this reason, the sacrament cannot be allowed to close in on itself: ‘the efficacy of the sacraments cannot be understood in any other way than that of the communication of the Word’ (226). ‘In thus experiencing concretely the consistence and resistance of this compact food, we experience symbolically the resistance of the mystery of the crucified God to all logic.’

The letter of the Scriptures wishes to ‘take over the body of the people’ and it is the sacrament that is ‘the great symbolic figure’ of this.

The sacraments allow us to see what is said in the letter of the Scriptures, to live what is said because they leave on the social body of the Church, and on the body of each person, a mark that becomes a command to make what is said real in everyday life. Thus, they are the symbols of the integration of the writing into “life,” the transit of the letter toward the body. (227)