On numerous occasions in my writing on social and political issues, I have drawn attention away from the issues that lie in the largely ephemeral foreground of our awareness to remark upon the radical changes that the technology of the Internet—and, in particular, the rise of social media—has occasioned in our sociality and discourse. These radical changes have altered the dynamics of identity-formation, of the ways that we relate to each other, and the locations and the processes of our conversations. It is, I believe, increasingly impossible to understand the features of the foreground of our public life without some awareness of the revolutionary effects of recent changes in this deep background.

It is not in least bit accidental that our societies are increasingly polarized, our relations increasingly reactive, our discourse increasingly failing to exhibit moderation and balance, our focus increasingly fixated upon competing identity groups, our processes of moral deliberation ever weaker, our politics increasingly characterized by viciously antagonistic populisms, authority and leadership increasingly ineffective, our populations increasingly distrusting or capriciously selective of experts, our media increasingly partisan and unreliable, people increasingly paranoid, our ability to distinguish spectacle from substance increasingly lacking, or our sense of self increasingly entangled in our political viewpoints. Along with numerous other features of the contemporary situation, these issues arise from or are exacerbated by the ever more powerful role that the Internet and social media play in shaping our discourse and society. As I have written pieces related to this subject on so many occasions before, I thought I’d devote this post to compiling a list of some of these, for those who have not already read them.

More recently, I have commented on the ways that online culture has shaped our politics and social relations in the age of Trump. In the first point of yesterday’s post on the subject of Trump’s executive order, I observed the manner in which online social media are the media of contemporary politics and help to explain the character of Trump’s presidency and our reactions to it. In this reality, we are reactively fixated upon the online spectacle, within which reality is often refracted in the most incredibly distorted fashion.

For instance, although we can complain about ‘virtue-signalling’ online, it is crucial to recognize that virtue-signalling is often simply a matter of using online social media naturally—online social media is a place where we are encouraged to say things in order to be seen by others. The entangling of personal identity and speech that online social media encourage is almost inescapably inherent to their character. Avoiding a preoccupation with speech as the projection of our identity and belonging requires a fairly purposeful determination to swim against the current of online social media as they actually function.

Three days ago, I wrote upon the ways in which the Internet represents a radicalization of principles of liberalism in a manner that threatens the social foundation of society upon which liberal institutions and practices must rest. I explored in some detail how each of the supposed liberal freedoms that the Internet maximizes have brought corresponding forms of oppression, fear, or constraint.

Back in November, I wrote about the manner in which the Internet and online social media decrease social trust:

Some of the factors that have given rise to our current situation are related to the current form of our media. The unrelenting and over-dramatized urgency of the media cycle, especially as that has been accelerated on social media, heightens our anxiety and reactivity. It foregrounds political threats and changes and makes it difficult to keep a cool head. When our lives are dominated by exposure to and reaction to ‘news’ we can easily lose our grip upon those more stable and enduring realities that keep us grounded and level-headed. Both sides of the current American election have been engaging in extreme catastrophization and sensationalism for some time. This has made various sides increasingly less credible to those who do not share their prior political convictions and has made us all more fearful of and antagonistic towards each other. It has also created an appetite for radical, unmeasured, and partisan action.

The Internet has occasioned a dramatic diversification and expansion of our sources of information, while decreasing the power of traditional gatekeepers. We are surrounded by a bewildering excess of information of dubious quality, but the social processes by which we would formerly have dealt with such information, distilling meaning from it, have been weakened. Information is no longer largely pre-digested, pre-selected, and tested for us by the work of responsible gatekeepers, who help us to make sense of it. We are now deluged in senseless information and faced with armies of competing gatekeepers, producing a sense of disorientation and anxiety.

Where we are overwhelmed by senseless information, it is unsurprising that we will often retreat to the reassuring, yet highly partisan, echo chambers of social media, where we can find clear signals that pierce through the white noise of information that faces us online. Information is increasingly socially mediated in the current Internet: our social networks are the nets of trust with which we trawl the vast oceans of information online. As trust in traditional gatekeepers and authorities has weakened, we increasingly place our trust in less hierarchical social groups and filter our information through them.

Our news online is increasingly disaggregated. A traditional newspaper is a unified and edited body of news, but online we read from a multitude of competing sources, largely sourced by friendship groups. As our news no longer comes as a package, exists within a click-driven economy, and is largely sourced for purposes of social bonding, sensationalism, catastrophization, ideological reinforcement, outrage, and the like are incentivized. In a world of so much easily accessible information, news is a buyer’s market and pandering to the consumer by telling them what they want to hear becomes a greater temptation. Coupled with the growth of non-mainstream media sources that are often much less scrupulous about accuracy, the result is a much less truthful society. Even formerly respectable broadsheets are now not above publishing tabloid-style articles and hot takes and clickbait akin to popular websites.

Within that post, I discussed the problems that this can cause for churches and pastors:

Many people now privilege online bloggers, speakers, and writers over the pastors that have been given particular responsibility for the well-being of their souls. The result is growing competition among Christian gatekeepers, which increasingly positions the individual Christian, less as one fed by particular appointed and spiritually mature local fathers and mothers in the faith, and more as an independent religious consumer, free to pick and choose the voices that they find most agreeable. Sheep with a multitude of competing shepherds aren’t much better off than sheep with no shepherds whatsoever.

In another post written around the same time, I observed the way in which the changing environment of our discourse is shaping our political reality, and the ways in which it is entangled with unhealthy gender dynamics. The following are some lengthy quotations taken from that piece:

It is imperative that we take account of the cultural changes brought about by the rise of social media. I have written upon these at considerable length in the past. One of the central points that I have made is that social media bring us too close together. Traditional forms of public discourse are effective in large measure through differentiating their participants: through status, office, time, physicality, intermediation, ritual, place, position, etc., etc.

Public discourse traditionally occurred in highly aerated and differentiated discursive environments, such as courtrooms and debating or parliamentary chambers. Yet online we are all placed into a more immediate contact with each other, in a ‘saturated social environment.’ Within this realm we are all peers and contemporaries, without differences in rank or station. It is often a gender-neutralizing and egalitarian realm, where every voice is equally valid. Online we also all function on the crest of the latest breaking wave.

Millennials are often castigated as a generation for their narcissism, self-preoccupation, and other such traits. However, in our defence, it should be noted that we are the canaries in the coal mine of a new ecology of society discourse, especially younger millennials. Many of us have been using online social media since high school. The rise of social media is akin to the first introduction of a mirror to a society in which people had never properly seen their own faces. We are now existentially involved in an online spectacle on social media, where we must rigorously perform our identities, acutely aware of the fact that we are constantly exposed to judgment.

Existing in such a context elevates our social anxieties. It fractures or overwhelms former contexts of solitude and withdrawal from society. It creates a socially saturated order and limits the possibility of heterotopic discourse. When people complain about the need for a ‘safe space’, it is important to bear this new social reality in mind. Where there are few genuine sites of retreat from society and where challenging discourse no longer can be limited to a heterotopic arena, people will naturally feel much more threatened by people who strongly disagree with them. This is perhaps especially the case for young women, who are far more naturally attuned to and involved in the ‘social’ dimensions of social and connected media (for instance, generally sending considerably more texts than their male peers). Without a ‘safe space’, they are denied a realm of care and social conflict becomes total. Their concerns on this front should not merely be dismissed.

I proceed to observe:

The closer that Twitter and Facebook bring this internationalist progressive class to each other, the more that this class starts to function as a ‘dense society’, characterized by intense peer pressure and a fixation upon how one appears to others. It is a new ‘village’ where public shaming can nuke a person’s reputation and career, where the circulation of rumours and gossip holds immense destructive power, which can be strategically deployed as threat or sanction. It is also a site where the crowd itself serves as an agency that can be appealed to in order to intervene when someone feels threatened.

These dynamics will have the effect of turning the political classes in upon themselves in a profound self-absorption. The conversation will come to be dominated by those issues that are most serviceable for managing the political classes’ internal relations and self-expression and maintaining their standing, rather than by the issues that really are the most important and pressing in the wider society.

Symbolism will tend to replace substance. Given the choice between talking about the compounding crises of automation in the Rust Belt or transgender bathrooms, they will choose the latter. Given the political classes’ turning in upon themselves, it shouldn’t surprise us in the least that the last few years have been dominated by precisely the sort of primarily symbolic social issues that are most useful for virtue signalling within the elite class (same-sex marriage, fights over transgender bathrooms, getting the first female president, Black Lives Matter protests, etc.). Online we also have short attention spans, which can produce series of polarizing outrages and emotionally gratifying causes, few of which require any grasp of the larger picture.

Finally, I remark upon the ways in which online social media can lead to a collapse of the agonistic and male-weighted realm of politics into the female-weighted sociality of polite society:

Places like Twitter are becoming our Versailles, establishing progressivism’s hegemony by creating a new stifling centralized polite society under its oversight, with everyone jockeying for position by cosying up to its values, yet alienating and disempowering the rest of the population in the process. Instead of disparate regional interests entering a heterotopic realm of agonistic contestation, many parties are gathered together in a shared socially saturated environment where they conform to powerful cultural norms for the sake of their social and political survival. They are gradually being detached from their locations of origin and the disparate interests for which they once advocated. In the process, the population at large is gradually cut adrift from the political classes. The feminization of the realm of political discourse will naturally risk the tendency of closing the political class in upon itself.

As this is a theme to which I have returned so often, I thought that I would take the time to assemble a collection of relevant links to other pieces of mine, from which a sense of the broader issues can be gleaned. The following pieces don’t provide a detailed and unified picture, although that is something which I’d love to produce at some point. However, they do represent some of the dots which you should be able to connect together. Perhaps they may encourage you, as they have me, to be far more cautious and discriminating in your use of the Internet and social media in the future.

Smartphones and How They Change Us

An interview with Tony Reinke, in which I discuss some of the ways in which smartphones and modern connected media have contributed to the rise of new forms of social relations and approaches to identity formation. The following are some quotations:

The Internet is chiefly ordered around the eye and its mode of perception. The Internet renders the world as a unifying spectacle and its users as spectators and image projectors (a reality that Guy Debord presciently predicted in his 1967 book, La societié du spectacle). This ‘spectacle’ increasingly mediates and intermediates our relationships with ourselves, our world, and each other, and detaches us from the immediacy of human experience, relationship, and our natural lifeworlds. The contemporary person, for instance, may not feel that they have truly had their foreign holiday before that holiday has been rendered in the form of Instagram pictures, tweets, and Facebook status updates. The Internet becomes a sort of mirror within which we incessantly regard ourselves, establishing a cosmetically enhanced presentation of our selves and our personal realities. While not dismissing the possibility entirely, I would highly caution anyone who trusts too heavily in a reality encountered through the mediation of the ‘specious’ realm of the spectacle. While the Internet can be of great service to real world communities, it is a poor substitute for them.

***

The advent of social media and mobile connected devices is, in certain respects, a development akin to the movement from a world without any clear mirrors to one where highly reflective surfaces are ubiquitous. Just as the physical mirror image powerfully mediates my sense of my bodily self, the virtual mirror of social media now powerfully mediates my sense of who I am as a relational and social being. If the physical mirror feeds many anxieties and obsessions with our bodily appearance, the mirror of social media has a similar effect for our sense of our selves within our communities and society more broadly.

Of course, although they can have a similar relation to our increasingly reflexive senses of self, our self-projections on social media are not perfect mirror images, but representations involving an element of control, as you observe. Our careful curation of our virtual representations is not unlike the application of cosmetics to conceal unattractive blemishes. Online we also have the advantage of highly selective self-representation, choosing to present only our most attractive angles and exclude much else from view.

In speaking about ‘control’, however, it is important that we recognize the degree to which our self-projections in the shared spectacle of social media are experienced as disempowering, alienating, and anxiety-producing by many. Our practice of ‘control’ may feel less like an act of taking charge than one of mitigating a new threat. Just as the mirror can torment people with the awareness of themselves as objects to the gaze of a judging other, the mirror of social media can come with a terrifying sense of exposure to social judgment (or a disorienting sense of alienation from the representations of ourselves that we see there). Also, while the mirror merely allows us to see what others could already see, social media pressures us to share with others something altogether more intimate, and not previously publicly visible: our self-representations.

***

I have found the insights of both Edwin Friedman and René Girard very helpful in understanding the dysfunctional dynamics of Internet argument. In their different ways, both Friedman and Girard appreciated the danger of and the potential for violence in communities that are related too closely together. Such dangers are not usually recognized or taken seriously: people presume that community and forces such as empathy are inherently and uniformly good things and that we just need more of them. However, Friedman and Girard both draw attention to the fact that undifferentiated communities — communities whose members are too closely related to and identified with each other — tend to produce violent and reactive herd-dynamics. Such communities act through collective instinct rather than through considered response. They stampede like startled herds of cattle and emotions whip through them like firestorms. The way that we speak of the movement of ideas, emotions, advertising, cultural products, and pieces of information online using the language of ‘memes’ and ‘virality’ is very telling. Our agency is diminished as we merely react to and become the bearers of mass movements of emotion and interest that have taken on a life of their own.

The dangerously undifferentiated character of social media is part of the appeal for many. It is this undifferentiation that enables people to feel such an intimate connection with other people online, to experience such a high level of emotional resonance. Being caught up in shared feeling, a common sense of outrage, or being collectively drawn to a shared focus of interest produces a pronounced and addictive feeling of togetherness and belonging. Yet becoming creatures driven by the reactive instincts of the herd is dangerous. The herd doesn’t deliberate. The herd doesn’t reflect and then respond. The herd runs according to the immediacy of impressions, rather than through the responsible act of interpretation. The herd can’t negotiate difference with maturity.

Social media breaks down many of the means by which we are capable of developing a self distinct from the herd and by which we are enabled to respond rather than react. Social media moves exceedingly fast, breaking down the differentiating factor of time. Online the natural differentiation established by physical distance no longer exists. With more delay in time comes more of an interval for reflection and less of a drive to arrive at conclusions and responses prematurely. The density of relations in social media often denies us the emotional and personal space in which we can act and think for ourselves without experiencing crippling peer pressure. Social media obscures the differences between social and personal location. On social media people are typically anonymous and interchangeable account users: their backgrounds and histories, families, neighborhoods, places in society, and psychologies are invisible to us, often leaving us unmindful of these realities. Social media also dulls our awareness of differences in social status, placing the voices of elders, leaders, authority figures, experts, and professionals on much the same level as that of the opinionated man on the street. Social media breaks down the distinctions between public and private spaces, bringing the disagreements of public spaces into those realms to which we would retreat and where we are more likely to feel threatened. Disagreements on Facebook feel more threatening to people for whom Facebook is their realm of connection and close relation and they are more likely to react instinctively rather than respond thoughtfully as a result. Social media collapses contexts, forcing different groups of persons who would otherwise be able to enjoy friendly relations at a healthy distance into close contact with each other’s threatening and stifling differences, rather than giving us all the space and the places within which to be distinct. Social media disguises the differentiation of bodies, diminishing our sense of other people in their ‘full-bodied’ personhood and difference from us.

***

I wonder whether, in the intensity of the audio-visual world of the Internet, with its clamor and its spectacle, we dull our awareness of a depth beyond its surfaces or of a reality beyond the immediate and the visible. As we enjoy a rich wealth of background music on tap, the unsettling reality of an open horizon of silence, with its intimations of the silent and invisible presences it may possibly contain, is far less commonly encountered. When this is coupled with the hypnotic dazzle of a visually diverting online realm, our preoccupied senses can leave our attention inured to any reality that might exceed the immediate and visible. I fear that our hyperkinetic, cacophonous, and riotous audio-visual environments erode the art of silent and attentive listening and with it our sense of the presence of the invisible.

***

A desire to feel connected to the immediacy of current events and the conversations that surround them is a trap that many of us — myself most definitely included — have often fallen into. As O’Donovan recognizes, our obsession with the new, with the ‘roar’ of the ‘breaking wave’ privileges first impressions over considered reflections, the immediacy of the present moment over the broad sweep of historical context. His remark upon our peculiar obsession with the news is worthy of reflection:

Every culture concerns itself with news-bringing in one form or another; most other cultures have been more relaxed about it. Perhaps simply because we have the power to communicate news quickly and widely, we are on edge about it, afraid that the world will change behind our backs if we are not au fait with a thousand dissociated facts that do not concern us directly. It is a measure of our metaphysical insecurity, which is the constant driver in the modern urge for mastery. (2014: 234)

In an age where news can travel around the world in a matter of seconds, it is easy to forget how peculiarly novel the urgency our swift moving news instills in us actually is (the news of the fall of the Alamo didn’t reach London for over two months). In the age where news travelled exceedingly slowly, time given to deliberation and reflection would feel considerably more natural. With an addiction to the news cycle we are in danger, not only of losing the natural ‘tempo of practical reason’ O’Donovan identifies, but of disengaging the process of practical reason more generally. For how many of us is the news cycle really material for practical deliberation, rather than an addiction to feeling ‘informed’ and engaged in the national conversations?

Read the whole piece here.

Twitter is Like Elizabeth Bennet’s Meryton

An article for Mere Orthodoxy in which, using the work of William Deresiewicz on Pride and Prejudice as a foil for my discussion, I explore the relationship between the form of our sociality and our capacity for sound judgment, careful deliberation, and healthy social relations. The following are a few quotations:

What the Internet and the mobile phone make possible is the establishment of a new ‘saturated social environment’, which shares a number of common features with the society of Meryton as Deresiewicz described it. Modernity has rendered us more detached from each other and more disembedded from particular contexts, yet our communications technology offers us a way seemingly to overcome this social alienation, providing us with media with which to ‘connect’ to each other. Our lives are caught between this profound condition of alienation and a sort of ersatz state of hyper-connection that substitutes for what we lack in our offline existence. While some might have expected the Internet and mobile phones chiefly to be used for the communication of information, their primary significance in most people’s lives is their provision for the communication of presence. The Internet often feels a lot less like an ‘information superhighway’ and much more like a virtual village, where, through countless intertwined lines of relationship, everyone is minding everyone else’s business.

In the mobile phone, technology has assumed an especially intimate form. It is a device that can be carried on our persons at almost all times. People have become so attached to and dependent upon their phones that they often struggle to cope for any extended period of time without them. With the mobile phone, we are never unconnected. Even when we are seemingly alone, we can enjoy access to the presence of thousands of other people. A single tweet or updated Facebook status can communicate our presence to the many people who follow or are friends with us. A short text can share a private moment with a close friend. Such communications are often without any significant informational content, but are rather ways in which we stay connected with each other.

***

Austen’s characterization of Wickham and Elizabeth’s conversation as one of ‘mutual satisfaction’ could no less appropriately be applied to the sorts of conversational dynamics that typify many contexts online. The ‘density’ of these environments and the closeness of the bonding within them produce a cosiness that is welcome for many, but which is generally quite resistant to contradiction, conflict, criticism, and genuine difference. Such characteristics and behaviours as likeability, empathetic connection, mutual vulnerability and mutual affirmation, personal resonance, relatability, and inoffensiveness are essential to the operation of such environments, but these characteristics and behaviours largely preclude openness to criticism and challenge of the group and its conforming members. Those who make firm criticisms will readily be classed as ‘haters’ or enemies of the group and driven out with hostility, while the group reaffirms itself and its members of their rightness and the vicious character of all opponents, reinforcing all of their prejudices and steadily inuring all members to criticism. Such communities will also often engage in rigorous ‘policing’ of deviant viewpoints and, like the stereotypical mediaeval villagers, will frequently enact swift and merciless mob justice upon those who do not conform as they ought. Alan Jacobs’ recent remarks about our rapid movement to a society that cannot tolerate difference are relevant here.

Austen insightfully recognized the manner in which our delight in tight-knit, pleasant, and agreeable communities—and in conversations marked by ‘mutual satisfaction’—renders us susceptible to deep distortions of communal discourse, knowledge, and judgment. When we are all so relationally cosy with each other, we will shrink back from criticizing people in the way that we ought, voluntarily muting disagreement, and will shut out external criticism, reassuring and reaffirming anyone exposed to it. In such contexts, a cloying closeness stifles the expression of difference and conversations take on a character akin to the ‘positive feedback loop’ that existed in Wickham and Elizabeth’s conversation, where affirmation and assent merely reinforced existing prejudices. In such contexts, communities become insular (a tendency that can be exacerbated by algorithms), echo chambers of accepted opinion, closed to opposing voices.

***

A crucial dimension of the online ‘village’ environment is the saturation of the social space of many persons to the point where they never are truly alone for a sustained period of time, precluding searching introspection, self-presence, and self-definition. Without such non-social spaces and times, the self will not easily be able to sustain any clear identity of its own over against the group, but will be caught up in the collective opinion and self. When groups and relationships so extend their intimacies that they leave members without a genuine reserve of non-social space, time, and identity—typically a sine qua non for persons holding positions of their own, rather than merely assumed from the group—groups forfeit the power of difference and contradiction to power growth and insight. In the socially saturated communities created by mobile phones and the Internet, all opinion has to be observant of group consensus and resist expressing any difference that might rise to the level of conflict.

***

The preceding remarks might leave some readers with the impression that the burden of healthy thought overwhelmingly devolves upon individuals, considered apart from their communities, that community is principally to be considered as an obstacle to thought. This is certainly not the case. Healthy thinking—not merely dysfunctional thinking—is communal in character and not a task it is wise to assume alone. Austen’s challenge to us is not that we all become a particular type of person—a potentially disagreeable agent of contradiction such as Darcy, for instance—but that we all play our part in shaping our shared spaces to be ones that are receptive and appropriately responsive to the necessary contributions of a Darcy, without adopting a new form of homogeneity in the process. Healthy processes of communal thought are naturally differentiating and allow for—indeed, they typically require!—considerable variation in gifting and preferred modes of interaction and continual individual and communal processes of making space for genuine difference—not just for the Darcys of the world, but also for the non-Darcys. Elizabeth’s example here is useful: even when she was not directly engaged in contradiction herself, she spoke and acted in a way that would afford Darcy ‘the rhetorical and emotional space’ that he would require were he to disagree with her. We are integral to the stifling power of online communities and each one of us can do much to counteract this, by giving everyone else the space within which to disagree with us without rancor, by welcoming open divergence of thought in friendly communities. We are also driving the hyper-sociality that the Internet and the mobile phone make possible, as we expect our friends and acquaintances always to be at our disposal. If we developed a habitual protectiveness and respectfulness of each other’s solitude, privacy, and right to disconnect we would be better servants of each other.

Read the whole piece here.

How the Internet Has Brought Us Too Close Together (and the Wisdom of Trolls)

I explore some of the themes of the Internet as a site of undifferentiation, also mentioned in the articles above. I discuss the way that the Internet has evolved from its earlier form into something rather different, especially with the rise of social media. I argue that trolls, while often dismissed as mere bullies and flamers, may occasionally have something to teach us. The following are some quotations:

The early Internet was a wilder and less known place, with a lot of obscure corners. The obscureness of much of the Internet meant that things seldom came to us: we had to invest time in looking for like-minded people and interesting conversations—or creating contexts where they didn’t previously exist—much like explorers venturing into previously uncharted territory. The obscureness of many corners of the Internet meant like-minded people would often find each other and interact largely undisturbed by people who were mere troublemakers, with no genuine investment in the conversation. It also meant that conversations were less likely to be flooded by the uninformed and unqualified and that such persons could be much more easily recognized and removed.

The early Internet did not lend itself to publicizing in the same way. Information spread less rapidly and it didn’t provide the opportunities for the firestorms of outrage and the viral movements of emotional charged reactions that we encounter in the dense human forests of the contemporary Internet and its social media. Together with the previous factor, this meant that distinct conversations were less likely to bump into each other. The early Internet didn’t have the ‘mass’ culture that the Internet has today.

The early Internet was much less intimate and was more socially differentiating. It was much less emotionally charged as a result. As differences occurred within more neutral space, things were less likely to become personal (the proximity of so much of our online discourse to the personal profile isn’t always a good thing). Some of my favourite interlocutors over the years have been pseudonymous and anonymous, because such persons often seek to retain such a separation between private identity and ideas. On the other hand, the early Internet was more social in some respects. In the early Internet, we were more likely to function as mindful and intentional ‘community-builders’ than as passive consumers experiencing community. Our blogs weren’t generally set up as private means for self-publication—or even in order to form or host communities in our private space—but in order to participate in, contribute to, and collaborate in the formation of a wider conversation. My most worthwhile interactions online typically occur in contexts that date from this period of the Internet, or that share its characteristics—private e-mail discussion lists, obscure interactions in less known quarters of the Internet, e-mail correspondence, etc. Sites like Facebook encourage a collapse of differentiated social interactions into a much less differentiated social space. Another of the strengths of the older Internet is the way that it encouraged more differentiated social interactions. For instance, I have created over a dozen blogs or websites in my time, devoted to a variety of different matters of interest, speaking to specialized communities, enabling far richer interactions as a result.

***

Trolling is also often a guerrilla tactic used by those with a natural affinity to something closer to the more anarchic culture of the earlier Internet against the groupthink that often arises in the mass corporate culture of the contemporary Internet. These sorts of trolls are often intelligent, self-aware, independent, long-term Internet users, intensely well-versed in Internet culture, who dislike the way that online culture is being reshaped to make it a friendly and ‘safe’ place for entitled and hyper-sensitive passive online consumers, curated and controlled by corporations, squeezing out the diversity, unpredictability, confrontation, vigorousness, independence, creativity, and agency that they highly value in the Internet culture that was once more accommodating to, because it was largely formed by, people not unlike themselves. As this post observes, the troll represents a threat to and disruption of the corporate vision of the Internet, where everyone is clearly and neatly defined, where all keep in line, and interact in a predictable fashion.

Trolls can take many different forms and some trolls are decidedly unpleasant personalities. However, at their best, trolls can greatly enrich our online world, ensuring that the Internet never fully succumbs to the state of the sleepy settlement or to corporate colonization, but always retains something of the strangeness and unpredictability of the frontier, where people need to keep their wits about them, where they must develop thicker skins and take responsibility for themselves, and where startling and illuminating discovery can still occur. At their very best, trolls, like Socratic gadflies or biblical prophets, can serve to unsettle societies’ and individuals’ groupthink and their complacent relation to the truth. Such irritants can be some of the most important members of society.

Read the whole piece here.

Too Long; Didn’t Read

Within this piece, I argue that the Internet shapes our reading practices in unhelpful ways. The following are some quotations:

Reading a long post isn’t easy to do and I admire and appreciate every one of my readers who do this. The Internet is a great enemy of sustained and undivided attention. Online, the mind easily flits like a butterfly from one thing to another, seeking diversion. The moment one thing ceases to absorb our interest, there are always a dozen more things clamouring for it. Whenever we experience a lull in our focus upon the activity we are currently engaged in, we can feel the temptation to check our e-mail, Facebook, or Twitter. The Internet frees us from the unpleasantness of boredom, it constantly stimulates us while sparing us the effort of deep engagement. The Internet is a realm of immediate accessibility, where patience and hard work are seldom required to get what we want. This can encourage a state of distractedness in us as users. While channel-surfing is typically something that people do only in order to find a show to watch for a half hour or so, ‘surfing’ the Internet—rapidly hopping from one thing to another—is more integral to our online experience and we don’t have to break from such a habit for long before we start to feel fidgety. Reading a long article online requires not only the devotion of time and energy, but, perhaps more significantly, a radical break of state.

Our natural state of mind on the Internet is impatient, hurried, distracted, lazy, reactive, and restive. In this state of mind we ‘browse’ and ‘skim’ for the things that we are looking for—the emotional kick, the objectionable statement, or the retweetable line—rather than reading and closely attending to things that may surprise us. Casual, rapid, unfocused, inattentive, fickle, and impatient engagement becomes the norm. We look at things for just long enough to get an ‘impression’ from which we can derive a snap judgment (‘like!’). In such a state of mind we are seeking for momentary diversion, emotional stimulation, and immediate usefulness. Our minds drift like flotsam and jetsam on the Internet’s waves. It should not require much reflection to recognize that this state of mind is utterly inappropriate for deep learning. Unfortunately, this is increasingly a state of mind that is haemorrhaging into our offline mindsets too. As soon as things become dull or we sense the slightest whisper of boredom’s approach we instinctively reach for our mobiles.

***

Online, people often expect that the things that they read should be ‘engaging’ and that being ‘engaging’ is necessary for good writing. Yet many of the most worthwhile pieces aren’t very ‘engaging’ at all. Rather, they require exertion and effort, a constant battle with tedium and an onerous commitment to a high degree of attention. Few people pick up Hegel for diverting evening reading, yet the disciplined reader will be immensely rewarded for the effort that they devote to reading such a thinker. The same applies to many long reads online—which are a breeze to read compared to Hegel. I must read at least a dozen brief ‘hot takes’ every morning, but while such pieces often make an immediate impression, the effort—and, unlike the hot takes, reading here does require the discomfort of effort—that I devote to reading ‘long-reads’ is considerably more rewarding in the long term. Looking back over the last decade, it turns out that the vast majority of the plethora of hot takes and brief ‘engaging’ reads were soon forgotten, while many online long-reads remain with me even after a decade has passed. Many people appreciate that a long-read, although it may demand much more from the reader, can be far more rewarding over time—in no small measure on account of the demands that it makes.

***

Without the natural barriers or costs to access, it is easy to develop a different mental posture in relation to the material that we read. We have not had to earn access to the material through effort and knowledge. As we normalize immediate and effort-free accessibility we can come to resent any demands such material makes upon us. Like programmes on the channels on our televisions, we resist their presuming any more than the minimum prerequisite knowledge of us. Rather than our earning access to material, we can come to think that it is our reading material that must earn access to our attention by being entertaining or engaging. As we expect material to come to us, we normalize both the more ‘passive’ modes of reading and the frothy and insubstantial yet emotionally engaging modes of writing that prevail online. The fact that Joyce’s Ulysses is easily available on the shelves of the ‘public’ library doesn’t mean that it is for everyone. We don’t judge Joyce for presuming such a daunting level of familiarity with the English literary canon and language of the average user of the public library because the manner in which the physical copy of Ulysses is materially accessible to readers is much less likely to produce confused notions about the degree to which it ought to be otherwise accessible to them. It is, I suspect, the fact that people are accustomed to reading material coming to them online that encourages a different attitude, one more similar to that which we bring to our TVs. Indiscriminate and frictionless accessibility of material encourages the notion that reading material online should be palatable to and make few demands of the reader. The reader envisioned by the writer should always be the generic online reader, as being more discriminating about one’s designed readership contravenes the natural modes of the Internet’s dissemination of material.

***

Just because our writing is, on account of the Internet, potentially materially accessible to a degree that was unimaginable thirty years ago doesn’t mean that it should be equally accessible in other respects. I believe there are great benefits to maintaining certain restrictions of access that force readers to earn access through effort, a prior level of understanding, and commitment to a time- and attention-costly process of reflection. Even though our media do not determine our discourses, an attitude that treats the potentials and tendencies of our technology as imperatives to be realized can produce its own form of technological determinism, as all other aspects of our discourse succumb to a false technological imperative. The Internet affords immense potential for increasing the speed, the sociality, the accessibility, the immediacy, etc. of our discourses and often our duty is to use the Internet in ways that actively resist these frequently discourse-stifling potentials. We don’t have to walk through every door that the Internet opens for us and often we must go to the effort of purposefully closing them. Sometimes we need to introduce a little friction to this frictionless world.

***

Readers, if they want to be part of the conversation, owe writers a lot and we should not hesitate to make demands of them. Readers owe writers a careful reading and interpretation. They are not just passive consumers towards whom we have a duty of sensitivity to ensure my words make a positive ‘impression’. Such a strong reliance upon impressions is for the lazy and the passive, who cannot cope with the effort and responsibility demanded by the act of interpretation. The reader is not king. However, when we start treating him as one, our discourse will easily decay into emotionally-baiting pablum directed at readers who merely focus upon how the words felt to them or what particular subjective impressions they were left with and constant quibbles about whatever objectionable ‘tone’ was occultly detected in the voice of the author.

***

While the reader may not be king, the writer isn’t either. The writer bears responsibilities to the reader who is prepared for them, to guide the reader’s understanding through their subject matter. Contrary to many people’s expectations, however, this doesn’t mean the writer must make this process easy for the reader. The writer’s priority is the effectiveness of the learning process for their intended readers, not its ease. In resisting the false ease that readers supposedly demand of us as online writers we will be better equipped to act as their servants. In resisting any sense of entitlement and making appropriately high demands of them, we will strengthen their capacities of reason and interpretation. Together we can work towards forms of discourse online where no one is merely excluded, yet all are, in ways appropriate to their capacity, furnished with the challenging path through which they can access true knowledge and participate fully in discourses to the degree their commitment and preparation suits them and their desire leads them.

Read the whole piece here.

A Lament for Google Reader/Why It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Google Reader

Two pieces in which I reflect upon the death of the RSS feed aggregator Google Reader, and the fate of reading on the Internet. The following are some quotations:

In short, services like Google Reader increasingly belong to a past age of the Internet. The social web is the future and the place where we now ‘consume’ our information. While the gap that Google Reader leaves may well be plugged by other services, the departure of Google Reader from this area is a sign of a steady shift in Internet culture away the sort of relationship with information that such a web feed aggregator represents.

And what is this particular relationship with information? A non-social, private, and individual one. My lament for the slow passing of this relationship with information arises from my conviction that this is often a much healthier relationship with information than the typical alternatives. The larger quantity of material that Google Reader enables me to read may be its primary purpose, but it is only one of its benefits and perhaps not even its greatest. It is the way that Google Reader allows me to read that I most appreciate.

***

On Google Reader, my reading is not primarily determined by whatever is making an emotional impression in the social web right now (although that will come through in certain of the feeds that I follow). Rather, I have the more difficult task of discovering and committing myself to certain reliable and thoughtful sources, sources that I will read consistently over the course of a number of years, whether they are posting material that produces a strong emotional reaction or not. Such a form of reading forces you to choose your interlocutors and sources carefully, to invest over a long period of time in the most worthy and rewarding of conversations, to get to know certain voices very well, and not to be too distracted by the latest wildfire of controversy. It encourages you to read the sort of thoughtful and challenging material that forms deep understanding, even though it may provoke little in the way of an emotional reaction.

***

Occasionally something awakens us to the scale of the changes that we are living through. For me, a recent article by Julian Baggini, in which he describes burning an old set of the Encyclopædia Britannica, provided one such moment. Its ponderous volumes, once familiar symbols of the body of human knowledge, have been rendered obsolete, practically replaced by online sources such as Wikipedia. An authoritative physical and published source, representing a consensus of an academic elite, has given way to the virtual and protean network of Wikipedia entries, where the once-sharp contours of human knowledge disappear and entries on the subject of Hegelian philosophy rub shoulders with those on Nyan Cat.

Both the passing of the hard-bound Encyclopædia Britannica and of Google Reader represent milestones in the digital age. They remind us that reading and our engagement with texts aren’t static realities, but quite changeable. New technologies make possible new ways of reading, but also call for discernment. While new contexts, media, and gadgets can powerfully serve both reader and text, there are many occasions when our reading can benefit from limits.

Today’s web pushes us to read more, click more, share more, and comment more, but there’s something comforting about less. As readers, we may also seek out a form that’s slower, quieter, simpler, and less distracting. Neither nostalgic resistance to new technologies nor wholesale and uncritical adoption of them is the answer, but rather a prudent and discerning understanding of the nature of our particular texts, our appropriate relationships to them, and the tools that facilitate those relationships.

Read the whole pieces here and here.

Very Rough and Rambling Jottings on the Church and Social Media

An assortment of thoughts upon social media, the body, the Church, and the sacraments. The following are a few quotations:

The body is a site of obstinacy and resistance. While it provides us with means of communication, it also renders us the object of the communication of others.

The body resists our desire to autonomy and pure self-determination. While an avatar could in theory be entirely customized to the desires of its owner, our physical bodies are largely unchosen. Even as the site of our speaking, our physical bodies are themselves spoken – spoken by culture, nature, and tradition. Our bodies are the site where subject and object, self and other, internal and external, identity and difference, humanity and world are bound together. The body renders pure self-possession impossible, ensuring that even in our speaking, we are spoken.

A preference for online over offline communication may spring from a desire to be liberated from our bodies as sites of the other’s determination. The body is the primary site of unchosen, given identities. The marginalization of the objectivity of the body in online interactions could in many ways be regarded as a resistance to the role of the other, most particularly the social third party, in the determination of our identities. The online self is primarily a self-created persona, rather than the individuating response to the prior summons of others who first name us. The online self can be a resistance to the determination of being spoken.

***

Many of the buzz words of the online world are words that refer to the overcoming of the resistance of the body. The world of online interactions is immediate, fluid, frictionless, overcoming all distance or separation.

The body intermediates between us and others. While it facilitates connection, by virtue of its objective character, its resistance to autonomous self-determination, and its rootedness, it also can be felt to obstruct communication, to stand between us and others, preventing us from relating to people immediately and on our own terms. The online persona can be an attempt to dispense with intermediation through the erasure of the body.

The body distinguishes and separates us from others: it sustains distance and alterity. This is most clearly apparent in the case of rootedness and physical separation. The body roots us in a certain location, in one particular place and set of family relationships, rather than any others. The body ruthlessly particularizes our identities and largely in terms of unchosen givens. The online persona is not limited by or bound to locality, but is free to pursue an identity that transcends this.

***

One of the things that I have noticed about online media over the years is that they tend to be better at facilitating certain forms of interactions over others. In particular, the Internet can be very good at enabling direct and immediate relationships, bringing two parties into an interaction uninterrupted, troubled by, or directed by any third party. What the Internet tends to be less effective at is the establishment of strongly mediated relationships, within which two parties relate to each other through the visible mediation of a third party or pole. At this point it should be stated that there is always a third party or pole of some sort. However, the Internet tends to weaken this third pole, rendering it invisible, exchangeable, or marginal. Even our access to the Internet tends to create a direct relationship with ourselves and the contents of our screens in a manner that places offline third parties firmly in the background.

Let me clarify what I mean by a ‘third pole’. A third pole can be an individual, a community, a subject of conversation, an institution, a context, an activity, an identity, a relationship, an attachment, an object of desire or worship, a cause, a symbolic or legal order, a narrative, or anything else of such a kind that mediates the relationship between two parties. On the Internet, the third pole of relationships is minimized, the first and second poles being placed in far more direct connection. The third pole is changeable, seldom if ever dominating in the interaction, and completely subject to choice.

***

In a fascinating article, Venkatesh Rao reflects upon the manner in which profound technological change renders itself invisible to us through a ‘manufactured normalcy field’. New technology is related to in terms of elastic metaphors and the extension of existing modes of interaction. Facebook extends the metaphor of the school yearbook. The Internet has extended and developed the metaphor of the text or document. Through these extended metaphors a sense of familiarity, which covers over the fundamental strangeness of the new technologies and their modes of interaction, is maintained. On occasions, such a normalcy field cannot be created or maintained and we have a sense of the profound and threatening strangeness of the new technology.

On account of the mythic character of technology and this manufactured normalcy field, we fail to perceive the scale of the profound changes that are occurring beneath our feet. In assessing the place of online media in our lives as Christians and as the Church, we must learn to step outside of the normalcy field in which we live and appreciate the future in which we live unknowingly in all of its existentially disorienting strangeness, as a place profoundly disturbing and unfamiliar to us.

Rather than assessing new technology in terms of its conformability to a manufactured normalcy field, we must rather assess it in terms of its more objective reconfiguration of our interface with our world and each other, and the modes and contents of our relations. I submit that such an approach will encourage a far less sanguine approach to new technologies and a greater measure of suspicion, even though we might find much within them that is of merit and worthy of use.

Read the whole piece here.

Online Discourse, Leadership, Progressive Evangelicalism, and the Value of Critics

I reflect upon the changing character of blogging, participation in social media, and their part in online discourse. The following are some quotations:

The strength of such old blogging communities was that they allowed for an engaged but aerated conversation. While the distinctness of various voices was maintained, they never stood on their own. Although there was plenty of pretension going around (all of the Latin blog names come to mind), there was less of a need to justify one’s blogging by having Something to Say. Most of us knew that we didn’t have a whole lot to say that wasn’t a recycling of the thoughts of much smarter people, but blogged as a means of engagement with a small community of online friends and peers.

Over my years of blogging, however, this dynamic seems to have changed. Christian blogging exploded, but those original communities I was part of soon thinned out and blogs became more isolated islands. Fewer people had active theology blogs and those who still did were less framed by a community of diverse peers. A number of us were uneasy as we felt that the sort of conversation that we were engaged in was being radically redefined. Rather than seeing our blogs as speaking into a particular community of people with deeper connections with each other, connections that didn’t exist only online, they were being regarded by readers as platforms for the general publicization of the bloggers’ viewpoints, which was not how most of us set out to write in the first place.

***

Perhaps one of the greatest factors in producing healthy, non-reactive communities, who feel a confident and secure sense of self-identity, is strong leadership. We so often focus upon Christian leaders as mere communicators of information that we seldom reflect upon the way that Christian leaders communicate emotional dynamics to their communities.

A leader sets the tone for a community. If they are highly reactive themselves, they will be the figure that sets the herd stampeding. However, if they can keep a cool head and respond rather than react (whether aggressively or defensively), their entire community will begin to share in their leader’s own non-reactive self-definition. This is one of the reasons why being intelligent and engaging isn’t sufficient for healthy online leadership.

Many bloggers exercise a sort of leadership online, setting the tone for large numbers of people’s responses. One of the biggest problems in such situations is not so much the content of teaching (although that is definitely an issue), but the way that the immaturity of persons who have been thrust into positions of great influence and limited accountability before they had learned to develop the self-control required to complement their considerable gifts can lead to the creation of deeply unhealthy dynamics in the communities that form around them. Great damage can result, much of which could be avoided if their scale of influence was restricted until greater maturity had been developed under the guidance of wise older mentors.

***

As bloggers we create contexts of communal thought and emotional (once again, in a broader sense of the word) engagement, and we must bear responsibility for what we encourage. We have more of an influence upon the tone of the conversations in our comments than we might like to admit. If we often can’t control our reactions, our comment threads and readers will start to be dominated by that dynamic. The blogger can be the spiritual immune system of a community, maintaining a non-reactive presence that encourages balanced and healthy thought and engagement. However, the reactive blogger can create great bitterness, hostility, fear, and anxiety, producing poisonous dynamics that damage lives and churches.

Reactivity can be intoxicating and is also very easy to create and encourage. It comes naturally to us. It feels great to be a member of the stampeding herd and it is hard to resist joining when everyone around you seems to be. Fostering non-reactivity in our communities is a much more challenging task and requires people who have first mastered themselves.

Read the whole thing here.

Information Addiction and the Church

Within this post I reflect upon the notion of information overload and our relationship with information. The following are a few quotations:

Just as food is seriously misunderstood if it is reduced to biological fuel, so communication ‘content’ is seriously misunderstood if it is reduced to ‘information’. Food is a mediator of relationships with our bodies, cultures, communities, families, world, nature, our core values, and our faith. Much of the food that we eat and most of the expectations that we have of it go far beyond what would be expected of something that was no more than biological fuel.

In like manner, ‘information’ is a mediator of relationships with our world, ideas, values, other persons, communities, identities, etc. The real issue is not quantity of information (suggested by terms such as overload or overconsumption), but the shifting way in which our relationships are being mediated in the modern world. For instance, our new forms of communication can lead to a sort of ‘malnutrition’ in our relationships, as touch is depreciated, and sight is overvalued.

***

The person who is addicted to information can’t get the big picture and discern meaning, as they are always frantically caught up in gathering fragmented, contradictory, and uncommunicative information, which leads to a failure of understanding and action. The person who is addicted to information is always second-guessing themselves, doubting their course of action, and losing the power to be decisive. The person who is addicted to information in the form of stimulation (or bombarded with advertising) is likely to become unable to fix their desire wholeheartedly on one thing and pursue it with an undivided mind.

The Internet enables and encourages this addiction in several respects. The Internet can be a crack house for information addicts, where we are surrounded by the substance, the habits, the addicts, and the pushers. On the Internet, information consumption and proliferation is the primary means of connection: if you limit your consumption and pushing of information in order to act, people think that you are dropping out and moving away from them. It is hard to opt out of the habits of the Internet while remaining in it and to set our own limits on our use, as people are constantly using the communication of information to us as a means of connection to us: if we resist we are not appreciated and can become isolated, as other offline means of social communication are less consistently employed (how many personal letters have you handwritten so far this year?).

***

The ends of information and its communication must be paramount in our minds all of the time. When the gathering of information becomes an end in itself, supplanting its communicative and formative purposes we may need radically to reassess our practice. ‘Information’ exists to mediate relationship and connectedness with the world, ourselves, each other, our visions, thoughts, ideas, passions, and feelings. Like a thickening lens, an accumulation of superfluous information can blur beyond recognition what it once brought into focus. It can dull and confuse the action that it once directed and sap the will that it once spurred.

Information must, therefore, be handled with care, moderation, and balance. This is the only way that we can be people who are both communicative and responsive. We need to identify the areas where an unhealthy relationship with information has enervated our action, engagement, and connection, whether by lack of communication, or by an excess of information leading to its breakdown. We also need to assess the ways in which our involvements online have shifted these relationships for good and ill. We need to think more rigorously about how to resist the dangers and temptations of the superfluous information on the Internet, while fully availing ourselves of the online information that is most valuable.

Read the whole thing here.

Concluding Notes

In my diagnosis of some of the problems of the Internet and online social media, something of my proposed solution should be apparent. Here I believe that Edwin Friedman’s book A Failure of Nerve, of which I have written an extensive summary with attendant notes here, has a lot to teach us. Friedman’s key insight—incredibly basic, yet profoundly illuminating, and widely applicable—is the importance of being self-differentiated in our relation to others. Self-differentiation involves our ability to maintain the distance and the difference from others that enables us to respond rather than react, to be engaged without being engulfed.

Perhaps the very core of all of my concerns about the Internet is that the medium undermines such self-differentiation, by breaking down the forms of natural differentiation that naturally exist in our daily lives. The result has been that of rendering us ever more vulnerable to the dominion of instinct, reaction, appetite, and passion over virtues forged through limitation, constraint, delayed gratification, submission to formation and discipline, and the struggle of deep communal belonging. While it doesn’t force us to be undifferentiated and reactive, it undermines a great many of the conditions that both make it possible for us not to be and which develop self-differentiated character within us.

Recognizing that the character of our current social and political crises is powerfully shaped by this lack of self-differentiation (on both individual and broader social levels) helps us to perceive that the solution necessarily requires a renegotiation of our relationship with our media. This renegotiation must aspire beyond mere individual and communal discipline to structural reformation of our online social media, to the formation of media that enable us to recover some of the healthy differentiation that we have lost, the ‘friction’ and the limits that can create healthy and enriching bounds for our lives and identities.

On

On

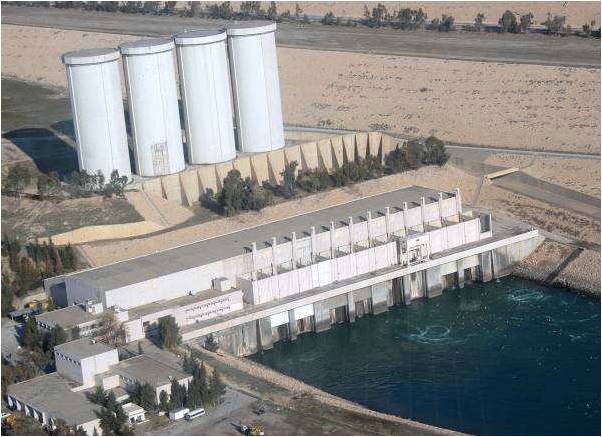

The Mosul Dam is failing

The Mosul Dam is failing