A few weeks ago I heard a sermon on Romans 6:15-23, during which a number of questions were raised in my mind about the way that the passage should be read. Seeing the second half of Romans 6 referenced in a piece I was reading this morning, I had cause to reflect upon it again. While I am not certain about whether the following is the correct way to interpret the passage in every respect, I think that it might help to provide a somewhat deeper reading than that which I have generally encountered.

The main detail upon which I am focusing is the theme of two ‘slaveries’ or states of ‘servanthood’. In the majority of the approaches that I encounter, it is the paradoxical dimension of this that is emphasized: the fact that we are released from slavery through slavery. While this paradox can be played up for rhetorical effect, I suspect that, on account of our particular cultural understanding of slavery, we are inclined seriously to misplace Paul’s accent here. As our focus is drawn to the paradoxical relationship between freedom and slavery within the passage (which is actually more of a set of contrasts than a genuine paradox), I believe that Paul’s primary point can be obscured. On account of how sharply the slavery/freedom contrast operates in our understanding, the contrast between the two forms of slavery and the fact that the ‘slavery of righteousness’ is a particular elevated status that we are more accustomed to speaking of in quite different terminology is not adequately recognized.

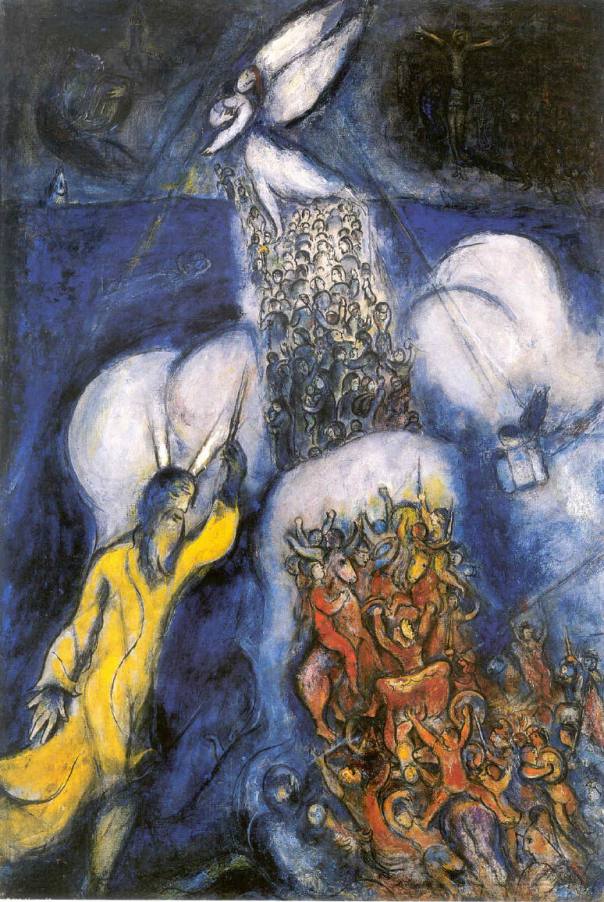

In moving towards a slightly different way of reading the passage, the primary clue that we can attend to is the fact that Romans 5-8 is rooted in the pattern of the Exodus narrative. As N.T. Wright argues in his article ‘New Exodus, New Inheritance’, a first century Jew hearing of liberation from slavery through water would have thought of the Exodus. Wright remarks of the larger pattern of Romans 5-8:

We could summarize the narrative sequence as follows: those who were enslaved in the “Egypt” of sin, an enslavement the law only exacerbated, have been set free by the “Red Sea” event of baptism, since in baptism they are joined to the Messiah, whose death and resurrection are accounted as theirs. They are now given as their guide, not indeed the law, which, although given by God, is unable to do more than condemn them for their sin, but the Spirit, so that the Mosaic covenant is replaced, as Jeremiah and Ezekiel said it would be, with the covenant written on the hearts of God’s people by God’s own Spirit.

The Spirit of God then leads the redeemed people of God to the Promised Land of new creation. As Wright argues, this pattern is homologous with the Old Testament narrative of the Exodus. Although I believe that Wright overstates how clearly apparent this pattern is, I believe that he is right to notice it.

Does this pattern cast any light on the meaning of the phrase ‘slaves of righteousness’ and upon why deliverance from slavery to sin should have the character of entrance into a new form of slavery? I believe that it does. Probably in large measure on account of the cultural understanding of slavery I have already mentioned, the story of the Exodus is popularly read in terms of a sharp slavery/freedom antithesis. However, the story of the Exodus itself is one of freedom from service in order to enter into another form of service (I’ve made this case in more detail in one of my 40 Days of Exodus posts).

The Exodus is framed by God’s insistence that Pharaoh release his people so that they can ‘serve’ him (Exodus 7:16; 8:1, 20; 9:1, 13; 10:3). In fact, in Exodus there is more reference to slavery/servanthood with reference to what the Israelites are moving to than with reference to what they are coming from. The book of Exodus is not chiefly framed by a slave/free contrast. In fact, Peter Williams argues that themes of slavery with reference to Israel’s state in Egypt are muted in Exodus. The book of Exodus (somewhat in contrast to Deuteronomy) speaks of bringing Israel out from bitter oppression, but does not typically characterize Israel as Pharaoh’s servants. Israel is God’s son and Pharaoh is wrongfully claiming and oppressing them.

When Egypt is spoken of as the ‘house of bondage’ (or the ‘house of servants’), it may well not be the Israelites to whom reference is being made, but rather the Egyptians. Throughout the narrative of the first few chapters of Exodus, consistent reference is made to the Egyptians as the ‘servants’ of Pharaoh (Exodus 7:10, 20; 8:3, 4, 9, 11, 21, 29, 31; 9:14, 20, 30, 34; 10:1, 6, 7; 11:3, 8; 12:30; 14:5). Israel is being delivered from the low status of cruel oppression by a land of servants (cf. Genesis 47:18-25) to consecration as the royal administrators of YHWH.

Entrance into this new service takes place at Sinai, where the covenant is made and where the tabernacle and its service are established. The setting apart of Israel as a royal priesthood at Sinai was their entrance into a new form of servanthood. As I wrote in my earlier post: ‘The story of the Exodus is the story of the movement from slavery to Pharaoh in the Egyptian house of bondage, building store cities, to service as royal priests in YHWH’s house and building the tabernacle.’

In summary, therefore, Israel didn’t cease to be servants in the book of Exodus (and the sharp linguistic and conceptual distinctions that we draw between ‘slaves’ and ‘servants’ are not present in the same way in Scripture). Framing the Exodus narrative in terms of our antithesis between slavery and freedom can cause us to miss or understate primary themes within the text, muddying the relationship between the second half of the book and the overarching movement of the narrative. The fundamental contrast in Exodus is not between slavery and freedom but between two types of service—service of Pharaoh and service of YHWH.

Peter Leithart, in this article, makes the case that the priest is a palace servant. The tabernacle/temple is the palace of God and the priest is the administrator of the royal household. What our focus upon the slavery/freedom antithesis and our casting of servanthood—which isn’t tidily differentiated from slavery—as a negative state causes us to miss is that being set apart as priestly servants of YHWH is a far higher status than mere freedom from Pharaoh. Thus, the true contrast should be between oppressive service under Pharaoh’s servants and elevation to the administration of the earthly palace of the Creator of the cosmos.

Returning to Romans 6, I believe that such recognition of the dynamic within the framing narrative can serve to bring the passage into a sharper focus. Now our reading of the passage will no longer be distracted by an undue emphasis upon a paradox of slavery and freedom, but will instead principally attend to the difference between two forms of service: the difference between cruel oppression under Sin and the exalted status of priestly service of God.

How might this enhance our reading of the passage?

The most significant change that it makes is that of bringing the world of the priesthood and the sacrificial system to the foreground of our imagination. Where our imagination would naturally reach to secular images of slavery (and, even then, most likely those of the antebellum American South than of the first century Roman Empire), we should now focus upon the tabernacle and temple and their service.

When thinking about the Law as it is discussed in the book of Romans, typically the focus is upon the Ten Commandments as the revelation of God’s will for all of humanity. Less attention is given to the importance of the Torah as that which established the service of the Tabernacle and the sacrificial system. As a result, we miss many of the key scriptural resonances of Paul’s language, not only of terms like ‘sin’, ‘death’, and ‘flesh’, but also of such things as ‘service’ and ‘holiness’.

If my suspicion is correct, then the theme of service that is introduced in chapter 6 provides a foundation upon which our reading of Romans 7 can operate, for instance. Romans 7 is describing Israel’s experience of priestly service under the Torah following Sinai. That priestly service revealed the Sin-Death-flesh nexus, primarily through the operations of death, uncleanness, and sacrifice within the Levitical system, rather than just on account of the reflexive knowledge of sinfulness as they looked at themselves in the mirror of the Ten Commandments. It is in the sacrificial system that Sin, Death, and the flesh truly reveal their character. While our salvation is homologous in many respects with Israel’s deliverance from Pharaoh and entrance into priestly service of God, within the new covenant recapitulation of the theme, the true priestly service that the Torah calls for will be rendered, not in the oldness of the letter, but in the newness of the Spirit of the risen Christ.

By bringing the world of the sacrificial system to the forefront of our minds, the subtle priestly themes of the passage start to emerge. When the passage speaks about ‘sanctification’ in verses 19 and 22, we should read this with a thicker sense: we are being consecrated for priestly service of God and access to his presence and ought to act in accordance with that fact. This consecration contrasts with the ‘uncleanness’ that previously characterized us. I also wonder whether the ‘lawlessness to lawlessness’ that Paul refers to in verse 19 might refer in part to the state of being without priestly status yielding action contrary to the will of God.

This, in turn, can strengthen the connection between the second half of Romans 6 and the first. This consecration for priestly service occurs definitively in the ritual of Baptism. As Leithart argues at considerable length in The Priesthood of the Plebs, the ritual of Baptism is patterned after the ritual of priestly installation in the Old Testament (cf. Exodus 40:12-15). Baptism ritually establishes us as priestly servants within the house of God, and now we must render the obedience of those who have received the honour of being consecrated for such service. While Leithart doesn’t draw the connection within the book, I believe that this passage reinforces his thesis.

Bringing the world of the priesthood, the tabernacle, and the sacrificial system to the foreground, we can also give more weight to possible sacrificial allusions within the text. When Paul speaks of ‘presenting’ and ‘offering’, it is the language of sacrifice. Coupled with this fact, it should be noticed that sacrifices were presented in the form of their members—separated into their constituent parts. As we present our members to God, we are being rendered a living sacrifice.

There is an analogy to be observed between the priest and the sacrifice. The priests and the sacrificial animals are consecrated to God in much the same way, becoming his possession. Priests had to be without disfigurement or defilement, like the sacrificial animals. They were brought near through a similar process. In Numbers 3, we see that God claimed the Levites for himself and in 8:11, we see that the Levites were all offered as a ‘wave offering’ to God. The priests were thus living sacrifices.

Priestly consecration also involved the presenting of members for service to God. As part of the rite of priestly installation, the priest had blood daubed on his right big toe, his right eye, and the thumb of his right hand (Exodus 29:20—as every Israelite male already had a blood rite performed on his penis, Leithart helpfully observes that this corresponds with the blood daubed on the four horns of the altar in Exodus 29:12). The ritual set apart the principal members of the body of the priest for divine service. Paul sees a similar thing occurring to the Christian. Having been washed with consecrating water (cf. Exodus 29:4), we must now present our members to God in service.

The themes that are more subtly present beneath the surface of the text in Romans 6 come to full and open expression in Romans 12:1: ‘I beseech you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, that you present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable to God, which is your reasonable service.’ The priestly sacrifice of our bodies to God in consecrated service, enacted definitively in baptism, establishes the continuing pattern of our Christian life from that point onwards. As we are baptized into Christ and his priestly death, our bodies and the service of our members are rendered sacrifices that are well-pleasing to God. We once laboured under the cruel and death-bringing bondage of the reign of Sin, offering up to him the service of our members, but now we have been delivered from his tyranny, washed and consecrated for priestly ministry to the life-giving Lord of the universe.

I’m reminded of Donald Bloesch’s observation that Christian freedom is ‘freedom for obedience,’ after reading this. The focus on the two types of service, as opposed to a more simple slavery/freedom theme is an important distinction.

My immediate response is much like that of the first commenter: perhaps what we need most of all to understand is that true freedom is found in service or “enslavement” to God. This is, of course, both deeply counter-cultural and counter-ego. But understanding freedom in this way might largely do away with all the circular debates about grace/freedom from the law giving licence to sin.

Another way to put it might be this: as human beings, we are always, inescapably, going to be slaves to something or someone. The only way to freedom is to be slaves to God.

(Somewhat off-track, this in response to your tweets about how your readership plummets when you write on Scripture)

I discovered your blog late last year and have been reading pretty regularly since. I admit I was not inclined to read this post when I saw the title, so I wanted to share my reason (b/c it may describe many more of your readers). I’m in school for neuroscience, and have no theological training whatsoever save for what I read in books. When you write about ideas that have impact on Christendom (or more narrow swaths of it), I can read and consider them because there’s enough in the argument to get me thinking. It doesn’t mean I understand *everything* but there’s enough for my critical faculties to consider your argument, and grasp what you’re saying.

I often about-turn when I know the piece primarily involves exegesis though b/c I have no means of evaluating your–or anyone else’s–exegesis. [Save for those ‘hinge-verses’ and chapters that are hugely consequential to my understanding of the Word (e.g. any verse that’s quoted in debates about election)]. I’ll just nod a lot, and wonder inside if you really are/aren’t correct.

So it’s not quite an aversion to writings on scripture, but a reluctance to engage in something that will be over my head and may well be that way for years to come. Does that make sense?

Have a great weekend!

Thanks for the comment, Peter, and for the thoughts! That makes sense. It is helpful to know where the readers of the blog are coming from.

Alastair –

reading this brought to mind another paradoxical correlation, viz. slavery (in a negative sense) is often referred to as being under a “yoke” cf. Gal. 5:1, Lev. 26:13, Duet. 28:48, etc. Consider then how this relates to Christ’s words in Matt. 11:29, 30. He says here, not that we are free now from *any* yoke at all, but that being under His yoke is easy b/c His yoke is light. The gospel implications being that the yoke is light b/c Christ takes on the full weight of the burden in His perfect life and substitutionary death in our place. So ten we are absolutely slaves who have been nought with a price and are now the possession of God, and yet “slavery” in His kingdom feels rather much more like freedom. Does that play into what you’ve seen in Rom. 6 at all?

I think that you are correct to see the possibility of a connection. There is quite a lot of biblical symbolism bound up with the idea of the yoke. The yoke is connected with servanthood (e.g. 1 Timothy 6:1).

The unequal yoking of the ox and the ass was the covenant union of the priestly people of the ox Jacob with the unclean people of Hamor (see the discussion here). Israel was under the ‘yoke’ of oppression in Egypt. God released them from that yoke (Leviticus 26:13), and placed them under his yoke, to serve in his field. As the bull under the yoke of the Torah, Israel was the priestly people and the temple was the field.(I have discussed such connections in much greater detail in this post). Israel refused to submit (Jeremiah 2:20; 5:5), so God put them under harsh and painful yokes, the yoke of their own oppressive kings and the yoke of foreign rulers.

Israel found itself unable and unwilling to bear the yoke of the Torah. When Christ came, the yoke of the Torah was removed as his new priesthood came with a change in the law and a new mode of service. The yoke is now that of Christ’s priesthood, founded upon his sacrifice and continuing intercession for us.

Thanks. That is helpful and clarifying. I’ll look into those other posts you linked to pursue it further.

God’s peace.

Hi Alastair – I believe viewing the events as part of a process is helpful. The pattern of “binding and loosing” found throughout Scripture, and referred to by Jesus, is helpful. It is the process of substitutionary sacrifice, or the two goats of atonement. Lot’s wife was “bound” (in sterility) that Sarah’s womb might be loosed. Isaac was bound that future offspring might be loosed. Joseph was bound that his brothers might be loosed (in a bad way). The Egyptian firstborn were bound that Israel might be loosed. Then Israel was bound by Covenant that the nations might be loosed. A husband is bound in marriage that his wife might be loosed. He is her freedom. Note that when Moses finds Israel in idolatry with the golden calf, the Lord says they have “broken loose.” We bind ourselves in prayer that others might be loosed. Paul was bound with a chain that the saints might be free. The apostles were bound for death that the Church might be loosed. Finally, satan was bound that the nations might be loosed. Identifying process makes sense of the Bible. I have a chapter on this in God’s Kitchen. If you’d like a copy, shoot me your address. (Mike Bull)

Thanks for the helpful thoughts, Mike!

Great piece of exegesis!