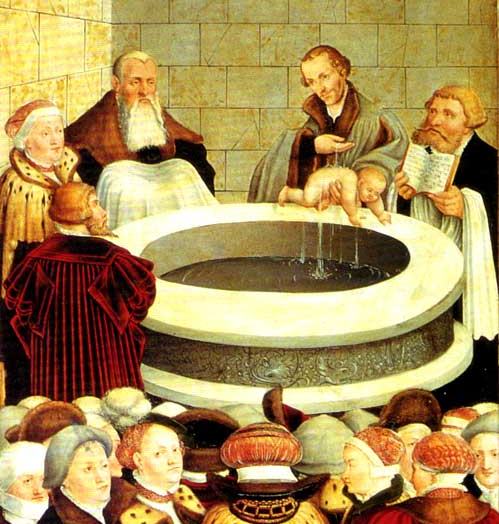

Phillip Melanchthon baptizing an infant, altarpiece in Wittenberg by Lucas Cranach the Elder and the Younger (1547)

Last month I had a lengthy and very stimulating discussion in the comments of one of my friend Andrew Wilson’s posts on the subject of credobaptism and baptismal efficacy. Andrew subsequently posted a summary of David Gibson’s paedobaptist position from that discussion.

He has now posted a summary of my position, and there is already a helpful conversation in the comments. Here are a few tasters of my comments:

Baptism functions much like adoption. It can occur before or after our conscious awareness and choice, but either way it changes our status and identity, makes us participants of a new context and life, and comes with new responsibilities and privileges. Even though adoption often precedes any choice of the child, we rightly presume that, as they grow up, they will willingly identify with the life and family into which they have been brought. While an adoption always achieves something, even when it ‘fails’, its presumed and desired effect is that of the adopted child maturing happily in a new loving context, responding with gratitude to the grace of their adoptive parents. The long term outcome of the adoption is fairly important. The child needs to be subjected to the long term practices of formation and inclusion that constitute ‘family life’ or adoption is emptied of much of its significance, becoming a hollow formality. Baptism is much the same.

And:

When Paul addresses the Church, he speaks of the realities that they have been given and made part of in terms of their proper reception, much as we do. When speaking generally about adoption, we don’t typically hedge our language to accommodate the cases where the child grows to reject their adoptive parents. In speaking of adoption, we appropriately assume that it will have its proper and desired effect and speak of it in such a manner. In the same way, Paul addresses the whole Church as the family chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world, even though some will fall away, all receiving the Supper as partaking in the ‘cup of blessing’, even though some will drink judgment to themselves, and all the baptized as receiving the benefits of incorporation into the life of Christ, even though some will turn their back on this.

Take a look at the rest here and see my much more detailed comments beneath the post that started this conversation off. Thanks to Andrew for hosting and advancing this worthwhile discussion!

Alastair,

I was really intrigued by Andrew Wilson’s characterization of your position as a sort of credo-paedo-baptism. Unfortunately, the comments section over at Andrew’s site has been disabled, so I wasn’t able to follow the discussion. Have you written anything else that outlines your perspective in more detail? And have you come across any other theologians, pastors, or resources that advocate an approach like the one you’re proposing? I’d like to keep reading on this, and any direction you can offer is much appreciated.

The following are my comments from that post. Unfortunately, I only have one side of the conversation.

Comment 1

I’ll try to do this quickly. This is my take:

First, the place of faith in Colossians 2:11-12 depends in part on translation issues. Rather than ‘through faith in the working of God’, my inclination would be to translate it ‘through the faithful working of God’. It is God’s faithfulness in his resurrection work that is being focused upon here, not our faith in God’s activity.

Second, I am with David: none of the options that you give tidily fit my position and number 3 is closest. Baptism really does something.

Third, like David, I think that passages such as Romans 4 are important background here. What most readers of Romans 4 miss is the incorporative significance of Abraham as a character. Abraham isn’t just an example of faith, but is the father of the faithful people of God (Richard Hays has some helpful remarks on this, I think). Abraham’s justification isn’t just a standard individual justification, but is a representative justification. We are all blessed in and not just like believing Abraham. The righteousness imputed to him is imputed to us in his seed, Jesus Christ. Our faith is ‘Abrahamic’ faith, a faith that grows out of and up into Abraham’s faith.

One of the important things to take from this is the fact that modern concepts of faith, built around the figure of the mature and detached individual—a notion with much in common with the tradition of philosophical and political liberalism—are somewhat at odds with biblical understandings of faith. In Scripture, faith is participatory and incorporative. Baptism is not really about my faith, but about incorporation into Christ’s faithful life. The faith that grounds baptism is his.

Faith is not just some private and internal reality for detached individuals but is also a posture of larger communities. While people may rightly protest that we have no evidence of infants within the household baptisms recorded in Acts and the epistles, the important detail to recognize is that the baptism of entire households was presented as the norm, even in cases where only the leading member of the household had been encountered. The communal life of the household was now characterized by faith and so those genuinely participating within it were to receive the sign of faith. The infant in a believing home is not an unbeliever but a full member of a faithful community, who must, in the natural course of human maturation, be brought personally and individually to own the communal identities and allegiances into which he or she was born. God is restoring the natural patterns of human relatedness he created, not working independently of them.

There are also differences on conversion here. It might be helpful to remember that many of the key people ‘converted’ and baptized in Acts weren’t unbelievers, but were believing Jews and God-fearers who were brought into the sphere of the new covenant. It is a redemptive historical and climactic/eschatological ‘conversion’ that lies behind many NT statements. The failure to appreciate the interplay between the ordo salutis and the historia salutis is a problem here. There is a danger of reading baptism too simply in terms of an ahistorical ordo salutis and failing fully to appreciate that it is about bringing us into the re-formed people of God in Christ. While a sort of radical transition may have been required of a faithful first century Jew or God-fearer or the unbelieving Jews and pagans that were their contemporaries, as a new age of God’s saving economy dawned, we should beware of presuming that the same thing is true of a child born into a believing home. The important thing is not conversion—and perhaps especially not as a conversion ‘experience’—but faith, by which the great Conversion effected in Christ is worked out in our lives by the Spirit.

So, in short, infants are baptized on the basis of faith. In the first place, the faith that grounds baptism’s efficacy is Christ’s faith, not ours detached from him. Second, the faith on the basis of which infants are baptized isn’t just ‘another’s’ faith, but is their faith too. To claim that it is another’s faith is to continue to frame matters in terms of the problematic anthropology of detached mature individuals.

Hope that this is of some help.

Comment 2

Baptism functions much like adoption. It can occur before or after our conscious awareness and choice, but either way it changes our status and identity, makes us participants of a new context and life, and comes with new responsibilities and privileges. Even though adoption often precedes any choice of the child, we rightly presume that, as they grow up, they will willingly identify with the life and family into which they have been brought.

While an adoption always achieves something, even when it ‘fails’, its presumed and desired effect is that of the adopted child maturing happily in a new loving context, responding with gratitude to the grace of their adoptive parents. The long term outcome of the adoption is fairly important. The child needs to be subjected to the long term practices of formation and inclusion that constitute ‘family life’ or adoption is emptied of much of its significance, becoming a hollow formality. Baptism is much the same.

I believe that Paul would presume that anyone baptized would be subjected to the formative ministries and life of the Church in the years that followed. Just as we naturally presume that the adopted infant won’t grow up to disown their parents and siblings but will grow into deeper relationships within the family into which they have been brought, so the baptized infant is really included in the life of the body—yes, really buried with Christ!—but must live out of this new life if their baptism is to be of any use to them. Baptism in situations where people are not thereby brought into the life of the Church is a negation of the reality of baptism, much as adopting a homeless child and leaving it out on the streets.

The issue of prudence is important here. An interesting thing to notice is the fact that the evidence seems to suggest that the early Church had a diverse practice when it came to baptizing infants. As in the case of something like adoption, wisdom is necessary to determine whether the baptized infant truly will become a participant in the life and formation of the Church. The proper subjects of baptism is less a matter of hard and fast biblical command and often more a matter of biblically informed wisdom. If both sides of the credobaptist/paedobaptist debates moved towards an appreciation of this, there could be much potential for rapprochement.

Comment 3

At the outset, I should make clear that my case doesn’t rest on the translation issue here. I am happy with either translation, though am inclined to go with the subjective genitive reading. I only raised the point because your position might be resting a bit more weight upon this detail than it might support. The ‘faith’ referred to in Colossians 2:12 is not so much our faith or Christ’s faith, but the faithfulness of God who raised Christ from the dead.

Christ’s faith—Christic faith—like Abrahamic faith, is a faith that belongs to the representative head, but also to all in him, as it flows from the head. Our personal faith is the outworking of Christ’s own model of faithfulness in us, as we are conformed to him by the Spirit.

When Paul addresses the Church, he speaks of the realities that they have been given and made part of in terms of their proper reception, much as we do. When speaking generally about adoption, we don’t typically hedge our language to accommodate the cases where the child grows to reject their adoptive parents. In speaking of adoption, we appropriately assume that it will have its proper and desired effect and speak of it in such a manner. In the same way, Paul addresses the whole Church as the family chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world, even though some will fall away, all receiving the Supper as partaking in the ‘cup of blessing’, even though some will drink judgment to themselves, and all the baptized as receiving the benefits of incorporation into the life of Christ, even though some will turn their back on this.

Unless I had reason to believe otherwise (very unlikely), I would speak of a baptized—I dislike the term ‘christened’—infant as receiving all of these things.

One of the underlying differences here might concern the implicit ‘location’ of the reality of our faith and, by extension, our salvation. In my experience, credobaptists are apt to think of it in terms of a state of heart within, to which the external event of baptism corresponds or responds in some manner. My belief is that our faith and salvation are both incorporative realities that overcome any internal/external dichotomy. Where does ‘putting on Christ’, ‘being buried with Christ’, and being ‘raised with Christ’ occur? Not in the detached privacy of the individual heart so much as in a more relational space, a space within which our hearts are nonetheless to be deeply engaged (for the Holy Spirit is present to us in the spaces of individual intimacy and privacy and not just in the congregation). The infant may not be self-conscious in the manner required for individual faith, but they are still deeply embedded and implicated in the relational space of human life.

Christian baptism is all about incorporation into Christ’s Baptism—his baptism in the Jordan, the baptism of his death, and the baptism with his Spirit at Pentecost. Each stage of Christ’s Baptism is given in response to his faithfulness in his vocation. This is the ‘reality’ at the heart of Christian baptism. Our personal faith is a participation in a reality that has its origins extra nos, but which works itself out within our subjectivity. As the reality at the centre of baptism is not the candidate’s own faith, but Christ’s, the integrity of the sacrament isn’t so contingent upon the manner of its reception and the identity of its subjects. Consequently, Paul will speak about baptism according to its own integrity (like the ‘cup of blessing’ in the context of the Supper), even in situations where the reality of the sacrament is not being received by those to whom it is administered on account of unbelief. In the case of infants, who are not unbelievers and who do receive it to a degree, their more limited subjective capacity for conscious and agentic participation is not allowed to establish the measure and character of the gift that they have been given and into a fuller reception of which, through the formation of and participation in the life of the Church, they are expected to grow.

I hope that I’m not raising more questions than providing answers here! 🙂

Comment 4

Sorry, I forgot that I hadn’t responded to this. I don’t see the statement as clearly excluding infants. Returning to the analogy of adoption, imagine addressing a large family of adopted children of all ages, including infants: ‘you were taken out of your old painful situation and made to share in a new loving family life, through trust in the goodness of your new parents.’ Would such a statement exclude the infants in the group?

In the case of infants baptized into the Church, they are raised with Christ into the new life of the people of God through faith. This faith isn’t yet a private, internal, and individual, but it still is a real faith in which they share and which effectively makes them part of the Christian community and participants in its life. Christianity is less an ideology than a new life. Infants have a ‘primal trust’ that binds them to their parents and their lives.

As I have argued, the NT speaks in terms of participatory faith: our faith is Abrahamic and Christic. It also presents us with a sort of vicarious faith. Christ’s miracles were closely related to the faith of those who received them. However, the deliverances were often received on the basis of a third party’s faith. For instance, when Jesus sees the faith of the men lowering the paralytic through the roof, he declares the sins of the paralyzed man forgiven (Luke 5:20). While the faith of the paralyzed man may also be in view here, the faith of his friends is part of the picture too. Mark 5:22ff, Luke 9:38ff, and John 4:47ff provide further examples of faith exercised on behalf of another. Likewise, God perseveres with the Israelites for the sake of their fathers. God is a family friend who, like us, doesn’t regard children as utterly detached from their parents.

The NT also speaks of a sort of indirect faith, a faith that may not involve the individual’s ‘personal relationship with Jesus’ in the self-conscious manner we tend to think of it, but which is nonetheless a genuine relationship. By relating to Christ’s brethren, people can be relating to Christ himself, as we see in Matthew 25. The child of believing parents is bound in primal trust to them, a bond that will develop into a more conscious and differentiated relationship with time. While they have not yet reached the stage of personal knowledge of Christ, they live in trust upon his faithful people.

With this bigger picture of faith, I think that the infant children of believers can be seen to belong to the people of faith.

Comment 5

It might be helpful to give some more flesh to the bones of the continuity/discontinuity debate on both sides. Things are a little too vague at the moment.

I see some fairly sharp contrasts between circumcision and baptism. They are rites that form rather different sorts of communities and draw upon different symbolism. I don’t believe that the particularities of sacramental symbolism is a matter of indifference and so believe that it is crucial that we attend to these differences. That circumcision was a rite involving blood performed upon the male sexual organ is significant, as is the context of its institution and the contexts of its employment. It is associated with the promise of seed and also seems to function as a cutting off of ‘flesh’ to protect the person from the greater cutting off of flesh. It is an excision of Israel for the nations, a permanent mark upon the flesh.

Baptism, by contrast, is a rite of inclusion, of new birth, of ordination to priesthood, less about the promise of the Seed than of being the seed. It is performed on people of both sexes and of all nations. It is a rite involving incorporation, dissolving oppositions, etc. It finds its roots in different events and narratives.

I have a lot of thoughts on the subject, but won’t get into them here. What should be recognized is that circumcision and baptism, while sharply contrasted in certain respects, belong to a single narrative (albeit in different acts) and are performed according to the will of one God. Thus far, I am sure that all of us will admit continuity. Some of the questions that need to be tackled are, for instance:

1. What sort of continuity exists between the nature of OT rites and that of NT rites? Is circumcision a ‘sacrament’ like baptism?

2. What sort of continuity exists between the people of God in the OT and NT, between Israel (and Gentile God-fearers?) and the Church?

3. Can the argument for infant baptism be made to rest upon an argument of the continuity of the mode of divine action with respect to the children of his people, irrespective of how circumcision and baptism relate as specific rites?

4. How about resting upon the continuity of an anthropological reality, viz. faith beyond common conceptions of it as only private, self-conscious, explicit, conceptual, internal, personal, and direct in its relationship to its object, such that infants can be seen to have faith too?

5. What about the continuity between creation and redemption? To what extent does redemption operate through and restore the channels of creation, such as the natural bond between children and parents?

Several other such questions can be raised, but I think that addressing these will help to tease out a richer concept of the continuity/discontinuity that is at issue here.

Thanks for making those comments available. They’re really helpful. Are there other thinkers or works that you’ve found particularly helpful in arriving at your conception of infant faith and its connection to baptism?

My thoughts on the subject are a synthesis of eclectic sources and I know that most other readers of them wouldn’t get the same points out of them. I don’t know of anything that articulates my position directly, in the way that I would.

Pingback: Pédobaptême et adoption — Alastair Roberts – Par la foi